Poems from the Urania Manuscript

Select versions to display:

Images

Transcription

Modernisation

Annotation

| Images | Transcription | Modernization | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

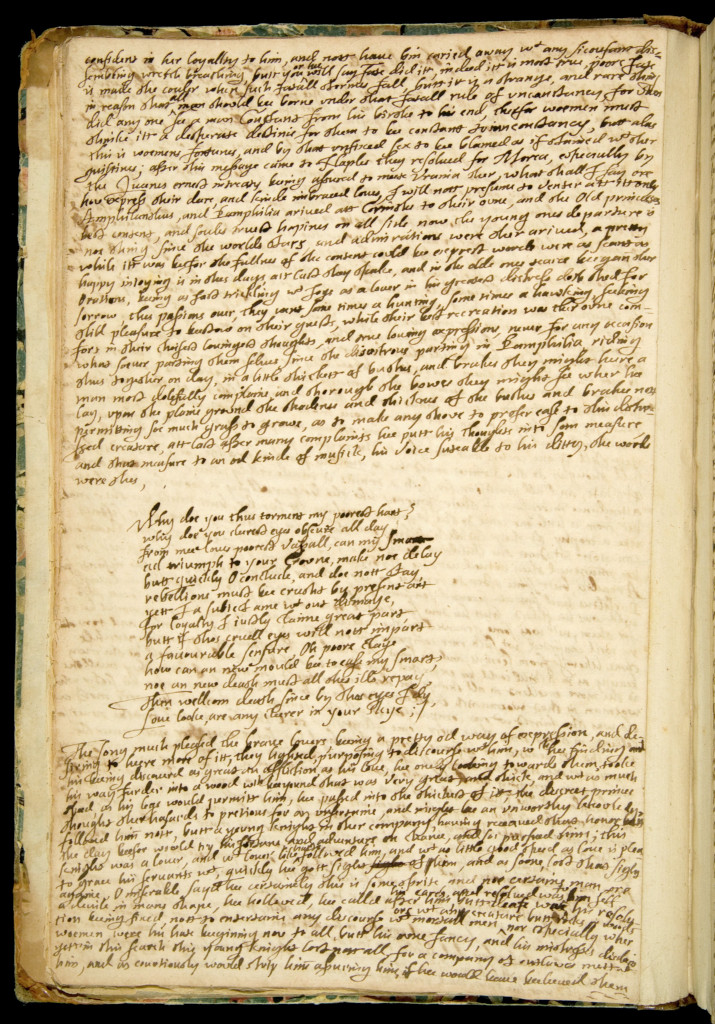

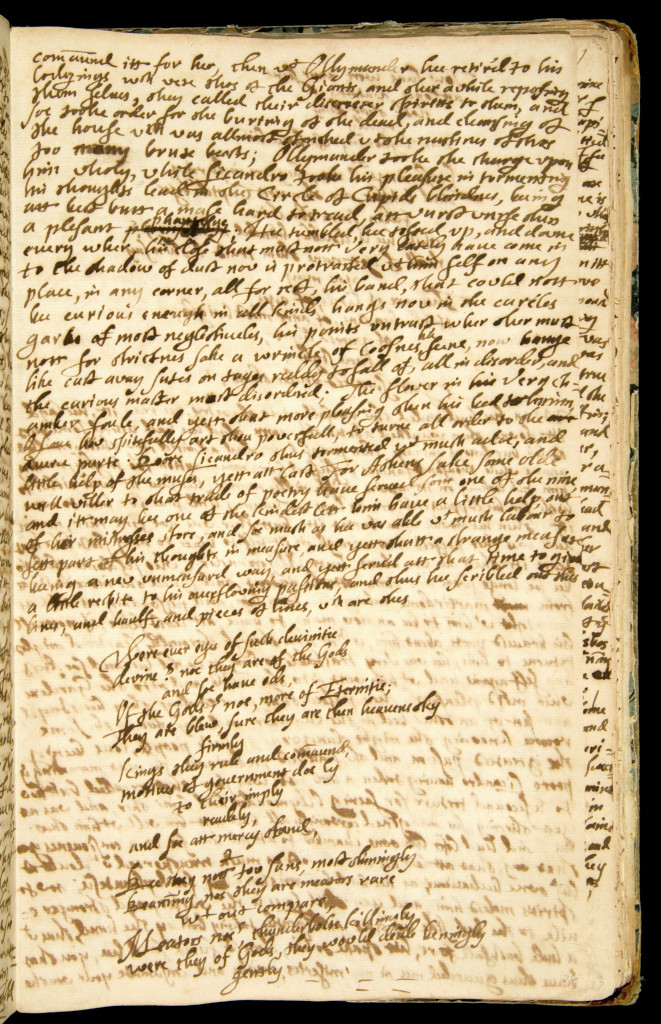

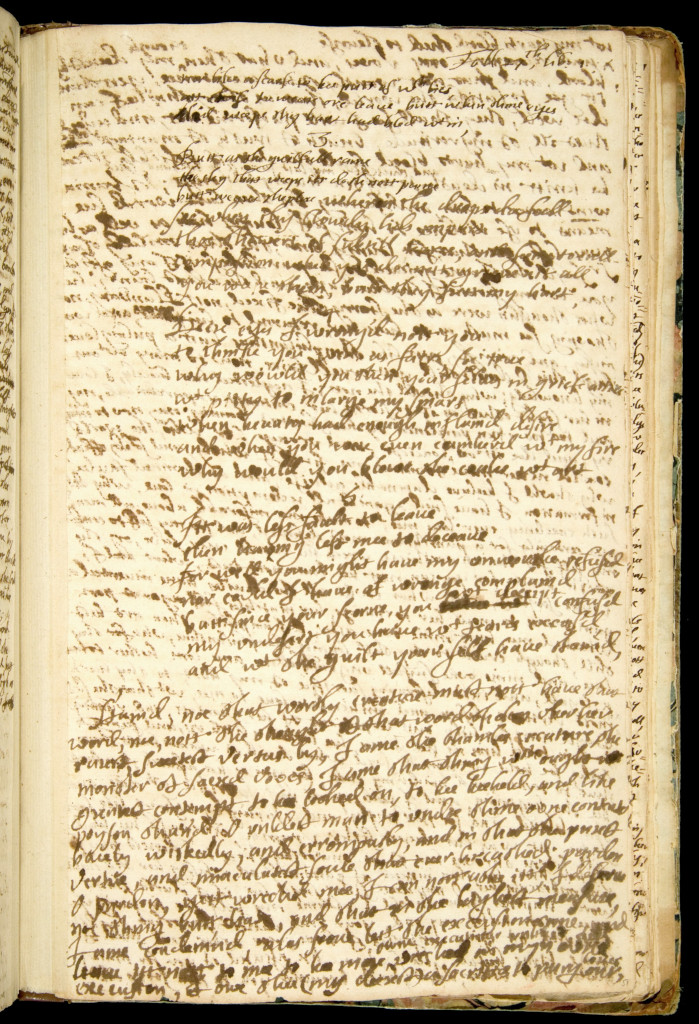

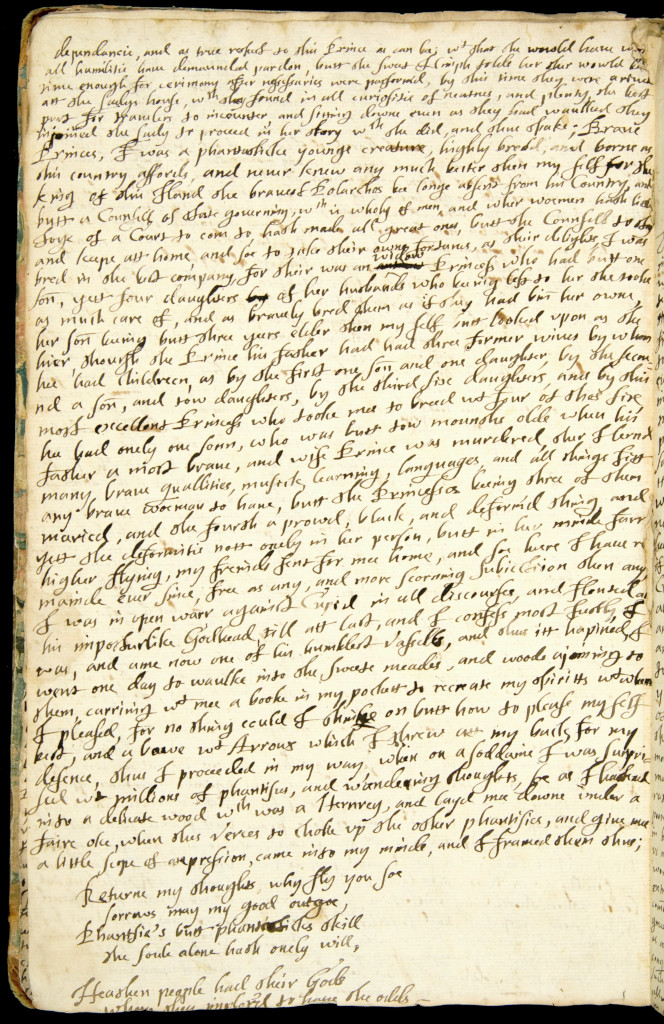

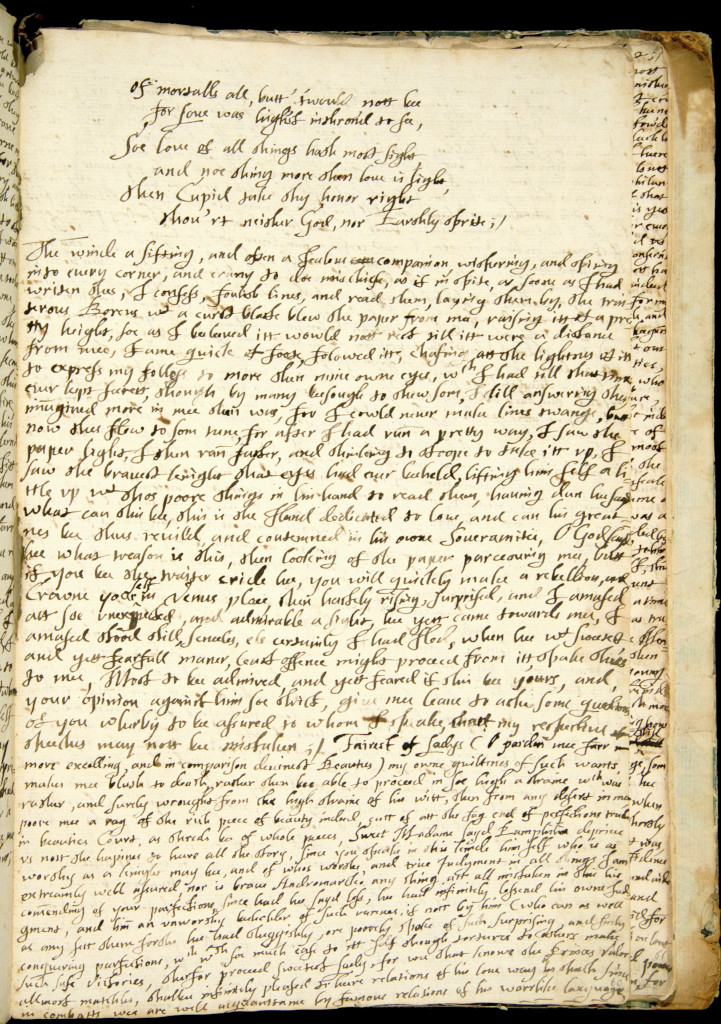

N1 Why doe you thus torment my poorest hart? why doe you cleerest eyes obʃcure all day from mee loves poorest vaʃsall, can my ʃmart ad triumph to your Croune, make noe delay butt quickly O conclude, and doe nott stay, rebellions must bee crusht by preʃent art yett I a subiect ame wt out dismaye, for loyalty I iustly claime great part, butt if thos cruell eyes will nott impart a favourable ʃenʃure, Oh poore claye how can an new mould bee to eaʃe my ʃmart? noe an new death must all thes ills repay, Then wellcom death ʃince by thos eyes I dy, Love looke, are any cleerer in your skye;/ |

N1 Why do you thus torment my poorest heart? Why do you clearest eyes obscure all day from me, loves poorest vassal? Can my smart add triumph to your crown? Make no delay but quickly oh conclude, and do not stay. Rebellions must be crushed by present art, yet I a subject am without dismay; for loyalty I justly claim great part, but if those cruel eyes will not impart a favourable censure, oh poor clay, how can a new mould be to ease my smart? No, a new death must all these ills repay. Then welcome death, since by those eyes I die, love look, are any clearer in your sky? |

N1 (p. 24): This is a song sung by the Prince of Corinth and overheard by Pamphilia and Amphilanthus. Unfortunately, music only exists for one song in the manuscript continuation of Urania (see N14), but we are told that this song is sung 'to an od kind of music' (24), although the prince's voice is 'suteable to his ditty' (24). Katie Larson (private communication) suggests that the idea of the song being odd might mean that it is unusual, rather than odd having a pejorative meaning, especially given the Prince’s ‘suitable voice’. (For song in Wroth in general see Katie R. Larson, The Matter of Song in Early Modern England, OUP, 2019.) The Prince’s song and state are provoked by his unrequited love for ‘a scornefull, senceles creature’ (27). The song is in the form of a sonnet using the kind of elaborate rhyme scheme found, for example, in Wroth’s uncle Philip Sidney’s ‘Astrophil and Stella’: ABAB BABA ABAB CC. heart: the tortured heart is a common image in Wroth’s poetry. obscure all day/from me: i.e. block out the day’s light. Note the clever use of enjambment where the break of the line mimics the obscuring. vassal: servant/slave. Rebellions: the political overtones in this poem are worth noting: the scornful lover is a ruler with a crown, rejecting the rebellion of the speaker, who is a loyal subject, but nevertheless one who will be crushed by ‘art’. Like so much of Wroth’s work, especially Urania, the vicissitudes of desire cannot be separated from anxieties over Jacobean foreign policy, forward Protestant demands for engagement in religious conflict, and some resistance to increasingly arbitrary monarchical power. poor clay: it what the body is fashioned from (in the story of Genesis). new mould: i.e. a refashioned body (clay in a new mould) as opposed to ‘welcome death’, which is the only escape from the frustrated lover’s torment. |

|

|

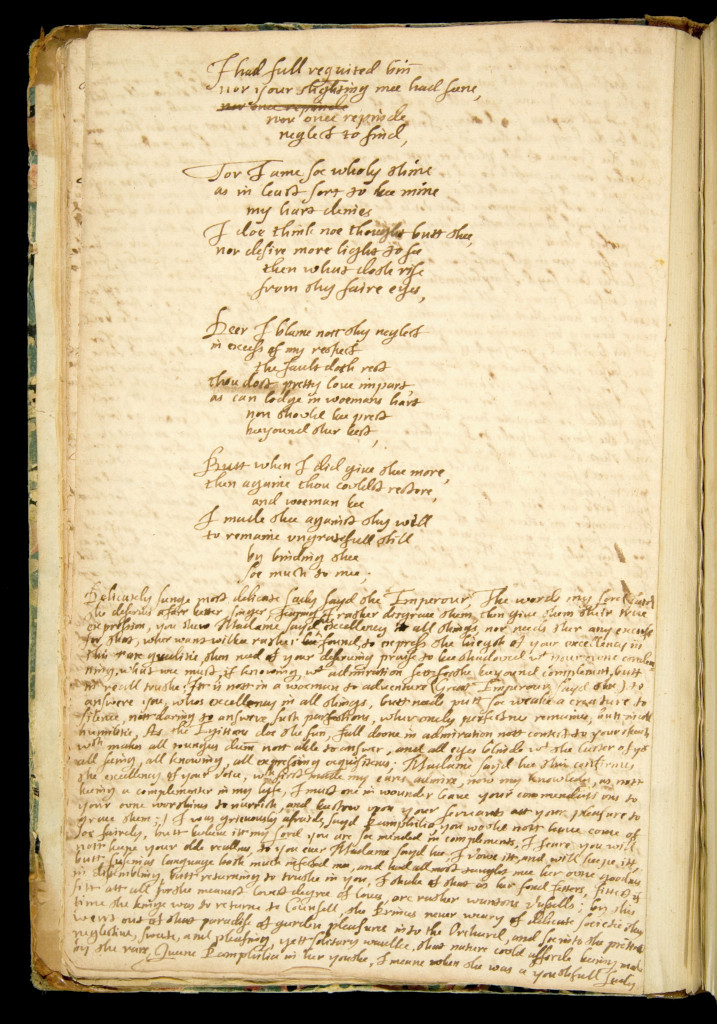

N2 Had I loved butt att that rate which hath bin̅ ordain’d by fate

to all your kinde; I had full requited bin̅ nor your slighting mee had ʃeene,

nor once repined

neglect to find,

as in least ʃort to bee mine

My hart denies I doe think no thought butt thee, nor deʃire more light to ʃee

then what doth riʃe

from thy faire eyes,

in exceʃs of my respect

the fault doth rest thou dost pretty love impart, as can lodge in woemans hart

non showld bee prest

beeyound ther best,

then againe thou cowldst restore,

and woeman bee I made thee against thy will to remaine vngratefull still

by binding thee

ʃoe much to mee; |

N2 Had I loved but at that rate which has been ordained by fate

to all your kind, I had full requited been, nor your slighting me had seen,

nor once repined

neglect to find.

as in least sort to be mine

my heart denies. I do think no thought but thee, nor desire more light to see

than what doth rise

from thy fair eyes.

in excess of my respect

the fault doth rest; thou dost pretty love impart, as can lodge in woman’s heart,

none should be pressed

beyond their best.

than again thou couldst restore

and woman be; I made thee against thy will to remain ungrateful still

by binding thee

so much to me. |

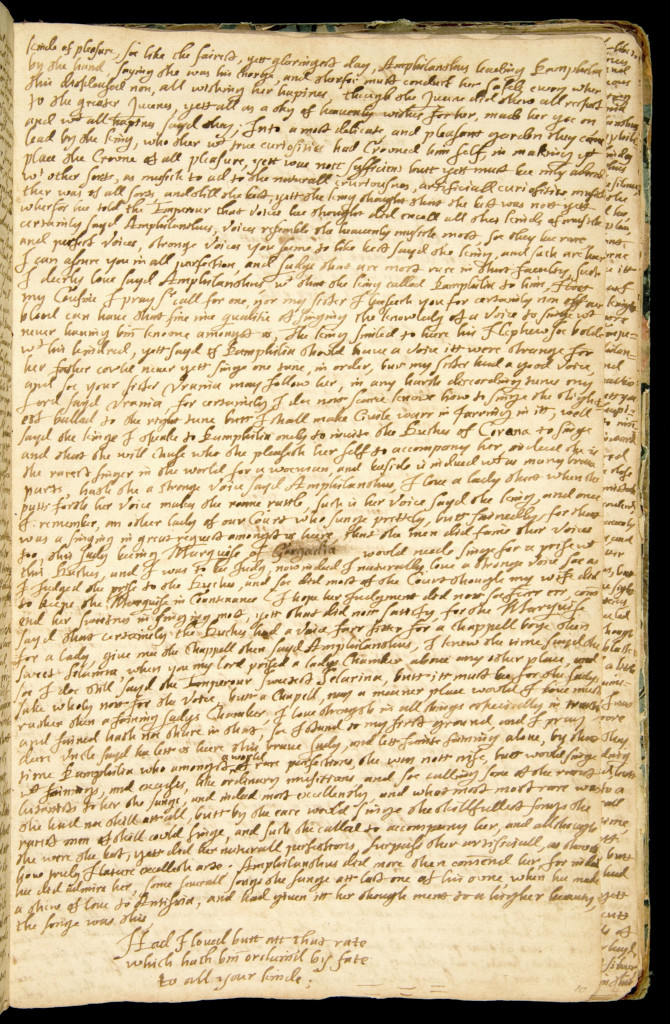

N2 (pp. 30-31): This poem is a remarkable example of the intersection between Wroth’s invented characters and their parallel figures ‘in real life’, as well as an example of how the fictionalisation enables Wroth to make some subtle points about her characters and about emotional and political contexts. This is a song composed by Amphilanthus and presented to Antissia ‘when hee made a shew of love’ to her (30), even though it was meant for ‘a higher beauty’ (that is, for Pamphilia). We are not told how the song has made its way from Antissia into Pamphilia’s repertoire; one can only assume that Amphilanthus presented it to her as the true recipient. The song was indeed written by William Herbert, Wroth’s lover and the ‘real life’ equivalent of Amphilanthus, and it exists in six extant manuscripts, ascribed to Herbert in three of them. So Wroth has taken Herbert’s song/poem, ‘given’ it to Amphilanthus, but imagined a situation in which Pamphilia would sing the song and thus underlines the irony of this male lament that is in a sense a have your cake and eat it too position: if only he had loved as women do, he would have been requited, but women are in fact unreliable, ‘ungrateful’, because of their being bound to the male lover’s desire. Because Wroth contrives to have the song sung by a woman rather than a man, it becomes part of her exploration of female desire in a world of casual misogyny. The fictional context is also ironic, because at this point in the narrative, Pamphilia is married to the King of Tartaria, and Amphilanthus is married to the Princess of Slavonia. Amphilanthus, in a fascinating example of politically significant wish-fulfilment, has become the Holy Roman Emperor, which would, if it happened in real life, offer a Protestant ascendancy in Europe, just as Pamphilia’s marriage offers a reconciliation between East and West. Manuscripts containing the poem: British Library Additional manuscripts: 25303, fol. 130v; 21433, fols. 119v-120v; 10309, fols. 125-125v; British Library Harley MS 6917 fols. 33v-34; National Library of Scotland MS 6504, fol. 98v; National Library of Scotland MS 2067, fols. 1-1v. For a detailed examination of the poetic interactions between Wroth and Herbert see Mary Ellen Lamb, ‘“Can you suspect a change in me”: Poems by Mary Wroth and William Herbert, Third Earl of Pembroke’, in Katherine R. Larson et al., eds., Re-Reading Mary Wroth (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 53-68. that rate: with that intensity, at that level. See Appendix (at end, after Poem 19) for images of the poem as it appears in four British Library Manuscripts. |

|

|

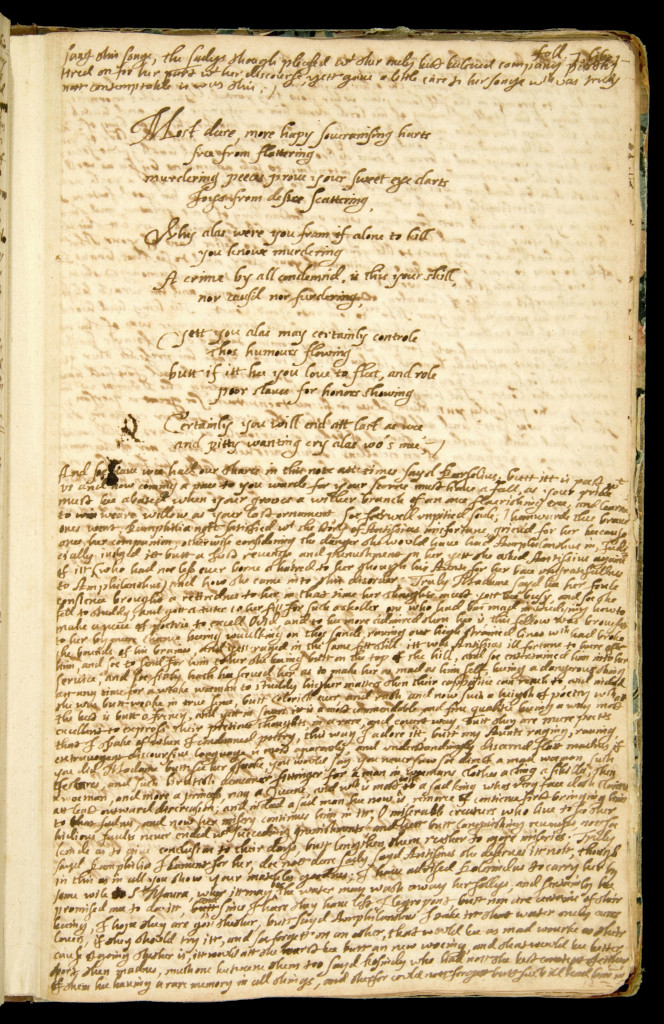

N3 Most deere, more hapy ʃoverainʃing harts

free from flattering murdering peeces prove your ʃweet eye darts

Joys from deʃire ʃcattering,

you knowe murdering A crime by all condemn’d, is this your skill,

nor cauʃ’d nor furdering,

thos humours flowing butt if itt bee you love to fleet, and role

poor slaves for honors showing

and pitty wanting cry alas wo’s mee;/ |

N3 Most dear, more happy sovereign[i]sing hearts,

free from flattering, murdering pieces prove your sweet eye darts,

joys from desire scattering.

You know murdering a crime by all condemned; is this your skill?

Nor caused nor furthering.

those humours flowing, but if it be you love to fleet, and rule

poor slaves for honours showing

and pity wanting cry, ‘alas, woe’s me!’ |

N3 (p. 40): This is a song sung by a farmer’s daughter named Fancy who was initially resistant to the idea of being tied down to a domestic life: ‘mee thought a little mirthe was better then ties att home, brawling of brats, monthes keepings-in, houswyfery, and dairies, and a pudder of all home-made troubles’ (38). But having been scornful of her lovers she began to be conscious of growing old and being alone, and accordingly now regrets that she rejected the offer of marriage from the equally aptly-named Love, son of the King’s chief herdsman. The poem itself takes the form of a sonnet in the so-called English rhyme scheme of ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG. The poem intertwines images of desire and images that have a political implication: so, for example, hearts are rulers (sovereignising) free from the kind of courtly flatterers familiar to any in the Jacobean court. The control exerted over the victim of desire leads to rebellion, so that the person apparently empowered will end up as abandoned and as wanting in fulfilment as the speaker and her allies. The poem can also be placed in the tradition of female-voiced complaint (for an analysis see Rosalind Smith, Michelle O’Callaghan and Sarah C. E. Ross, ‘Complaint’, in Catherine Bates, ed., A Companion to Renaissance Poetry (Wiley Blackwell, 2018), pp. 339-52.), where ‘woe’s me’ is the cry of those who are abandoned by their lovers. dear: punning on most valuable and most beloved. sovereignising: ruling over (like a sovereign). murdering pieces: pieces are guns (that murder). Nor caused nor furthering: the ‘murder’ is the rejection of the one who desires, so there will be no advance possible. humours: in humoral theory, the four humours (yellow and black bile, blood, and phlegm) represented bodily and psychological states. By the 1620s the idea included the notion of what we might characterise as sensations and feelings, as alluded to here. fleet: from flout: reject or sneer at. role/poor slaves: this may mean rule poor slaves, or more obscurely roll as in disturb. |

|

|

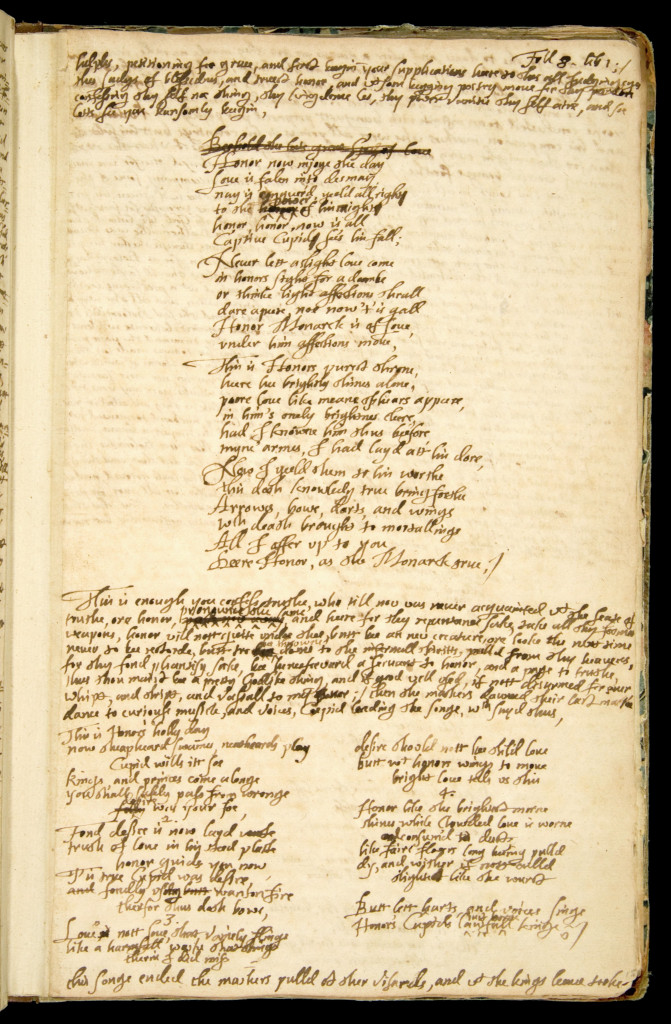

N4

Honor now injoye the day Love is falen into desmay, nay is conquer’d, yeeld all right to the honor, honor, now is all Captive Cupid

in honors ʃight for a doombe or thinke light affections thrall dare apeere, noe now ’t’is gall Honor Monarck is of Love, vnder him affections move,

heere hee brightly shines alone, poore love like meane sphears appeere, in him’s onely brightnes cleere, had I knowne him thus before, myne’ armes, I had layd att his dore,

this doth knowledg true bring forthe Arrowes, bowe, darts, and wings wch death brought to mortallings All I offer up to you Deere Honour, as the Monarck true;/ |

N4 [‘Behold the great God of Love’] Honour now enjoy the day, love is fallen into dismay, nay is conquered, yield all right to the power of his might. Honour, honour, now is all, Captive Cupid, sees his fall.

in honour’s sight for a doom, or think light affection’s thrall dare appear, no now ‘tis gall. Honour Monarch is of Love, under him affections move.

here he brightly shines alone, poor love like mean spheres appear in him only brightness clear. Had I known him thus before, mine arms I had laid at his door.

this doth knowledge true bring forth, arrows, bow, darts, and wings, which death brought to mortalings, all I offer up to you dear Honour, as the Monarch true. |

N4 (pp. 47-48): This poem comes from a masque staged by Pamphilia’s husband, Rodomandro, King of Tartaria. Wroth herself participated in the elaborate masques which were such a feature of the entertainment at King James’s court, dancing in Ben Jonson’s Masque of Blackness in 1605, for example. There are a considerable number of masques staged and described in both parts of Urania. The masque was rather like a combination of drama, opera and ballet, with spectacular scenery and special effects. The women who participated in masque performances, such as Wroth, had to have a considerable level of skill. This particular masque features masquers dressed ‘after the Tartarian fashion’ (46). The masque involves Cupid being berated by Honour for his wanton behaviour, and Cupid is in this process stripped of his bow and arrow and his wings. This song is Cupid’s response: a plea for forgiveness and a recognition of a higher power involved in Love. The masque and accompanying songs have some associations with the treatment of desire and of the figures of Cupid and Venus in Love’s Victory. Crossed out line: this may well have been more of a title than the first line of the poem, referring to Cupid. Honour: Honour is personified in the masque as outlined in the romance. fall: so Honour has replaced Cupid. doom: i.e. a decree, a judgement (OED). Honour, unlike Cupid, will not preside over a ‘light’ love, only a serious one. mine arms: so Cupid will lay the weapons that cause humans such anguish through their desire at Honour’s feet. mortalings: i.e. mortals, who in this image are subject to mortality and to the pains of desire. |

|

|

N5 1. This is Honors holly day now sheapheard ʃwains, neatheards play Cupid wills itt ʃoe kings, and princes come alonge you shall ʃafely paʃs from wronge

Fond deʃire is now layd waste truth of love in his stead plaste honor guids you now, ‘T’is true Cupid was deʃire,

therefor thus doth bowe,

Love”s nott Love, that vainely flings like a harmfull waspe that stings therin I did miʃs deʃire should nott bee stil’d love butt wt honors wings to move bright love tells vs this

Honor like the brightest morne shines while Clowded love is worne and conʃum’d to dust, like faire flowrs long being pulld dy, and wither if nott culld slighted like the wurst

Honor’s Cupids la̭w̭fṷll iust borne [‘iust borne’ inserted above] kinge;/ |

N5 1. This is Honour’s holy day, now shepherd[s], swains, neatheards play, Cupid wills it so. Kings and princes come along, you shall safely pass from wrong, desire was your foe.

Fond desire is now laid waste, truth of love in his stead placed, honour guides you now. ‘Tis true Cupid was desire, fondly using wanton fire, therefore thus doth bow.

Love’s not Love, that vainly flings like a harmful wasp that stings therein I did miss. Desire should not be styled love, but with honour’s wings to move; bright love tells us this.

Honour like the brightest morn shines while clouded love is worn and consumed to dust. Like fair flowers, long being pulled, die and wither if not culled, slighted like the worst.

Honour’s Cupid’s just born king. |

N5 (pp. 48-49): This song concludes the masque of which N4 is a part: with this song, we are told ‘the masquers danced their last dance to curious voices, Cupid leading the song, which said thus’ (48). The song continues the theme of Cupid conquered by Honour. shepherds, swains, neatherds: these are three pastoral figures: a swain is a country lover, a neatherd is in charge of cows as a shepherd is of sheep. desire was your foe: Wroth interrogates desire in much of her writing; here the quelling of Cupid allows for an escape from the control exerted by desire and in the song desire is replaced by love. |

|

|

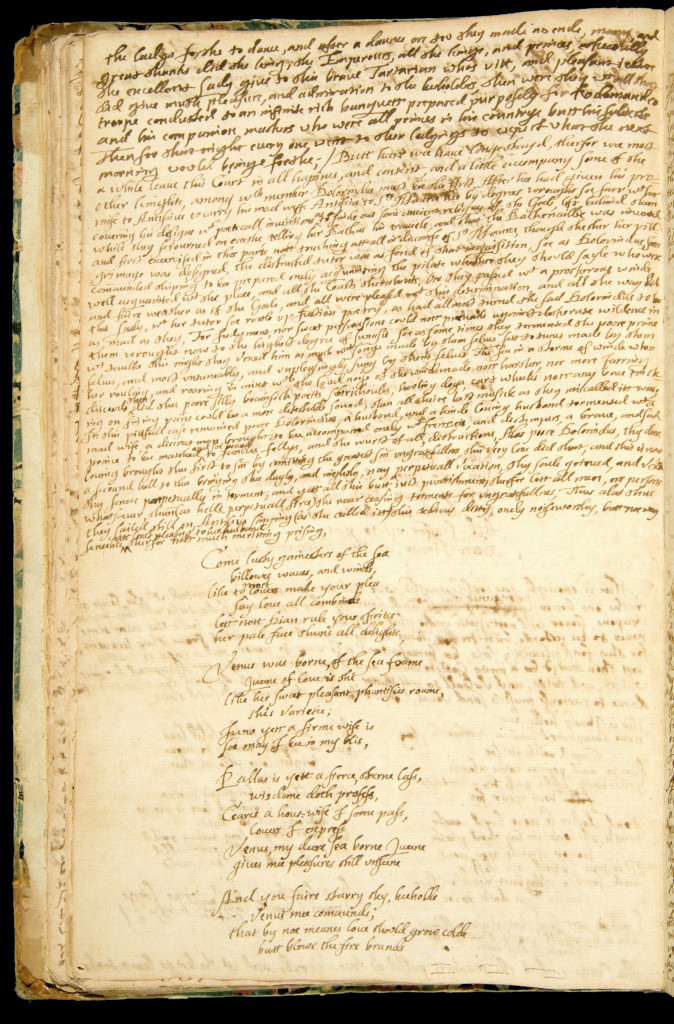

N6 Come lusty gamesters of the ʃea billowes waves, and winds, Like to ̭most [‘most’ inserted above] louers make your plea ʃay love all combinds lett nott Dian rule your sprites her pale face shuns all delights,

Queene of love is she like her ʃweet pleaʃant phantiʃies roame, this varietie; Juno yett a firme wife is ʃoe may I bee in my blis,

wisdome doth profeʃs, Ceares a hous=wife I ʃoone paʃs, lovers I expreʃs Venus, my deere ʃea borne Queene gives mee pleaʃures still vnʃeen

Venus mee com̅aunds, that by noe means love should grow colde butt blowe the fire brands Solls best heat must fill our vaines, thes are true loves highest straines, |

N6 Come lusty gamesters of the sea, billows, waves and winds, like to most lovers make your plea, say love all combines, let not Dian rule your spirits her pale face shuns all delights.

Queen of love is she, like her sweet pleasant fantasies roam this variety. Juno yet a firm wife is, so may I be in my bliss.

wisdom doth profess, Ceres a housewife I soon pass lovers I express. Venus, my dear sea-born Queen, gives me pleasures still unseen.

Venus me commands, that by no means love should grow cold but blow the fire brands. Sol’s best heat must fill our veins, these are true love’s highest strains. |

N6 (p. 51): This is a song sung by Antissia during a fit of madness which will eventually be cured later in the narrative. Antissia is, like Pamphilia, in love with Amphilanthus, and his eventual rejection and also it would seem her creative impulses drive her into madness. Antissia goes on to marry Dolorindus, the King of Negropont. Antissia’s symptoms include taking on an equally unbalanced tutor in poetry. This particular song is sung while Dolorindus tries to deal with Antissia’s madness; it is described as a ‘tedious ditty, only noiseworthy but no way sensible’ (50). It is difficult to assess a poem/song which within the narrative is meant to be tedious and unworthy. lusty gamesters: gamesters can be sportive people and lusty can simply mean strong, but paired together they suggest sexual adventurousness (OED has gamester meaning someone who is licentious or we might say sexually adventurous, as a current meaning in the early seventeenth century). Dian: Diana, Goddess of the hunt, traditionally associated with chastity. spirits: where Wroth write ‘sprites’ she intends spirits, a word which carries a complex set of associations ranging from the modern idea of spirit as a person’s vigour (as in spirited) through to the idea of one’s own nature in a metaphysical sense. In a notable sonnet from the ‘Pamphilia to Amphilanthus’ sequence, ‘When everyone to pleasing pastime hies’ Wroth depicts the speaker as seeking respite from court vanities as she talks ‘with my spirit’. Venus: goddess of love, as in the famous painting by Botticelli, Venus, the Roman equivalent of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, was said to have been born from the sea foam. Juno: goddess of love and marriage, wife of Jupiter. Antissia is stating that even in her ‘bliss’ (which implies possible sexual abandonment) she wants to be a ‘firm wife’. Pallas: Pallas Athena, goddess of war and wisdom. Ceres: goddess of agriculture, she symbolises fertility and was therefore associated with wedding ceremonies. Sol’s: the sun |

|

|

N7 This night the Moone eclipʃed was alas, butt quickly she did brightlier shine devine, prognosticating by ʃweet raine that all things showld bee cleere again,

and flowe, Coole drops ʃweet moisture, flowers bring to spring Which fruict bring’s forthe, and ʃoe shall wee live hopefully all good to ʃee

and crost though in Antipides nott quite bereft nor left, Butt in iust courʃe shall come againe, And wt pure light both shine, and raigne; |

N7 This night the moon eclipsed was alas, but quickly she did brightlier shinedivine, prognosticating by sweet rain that all things should be clear again.

and flow, cool drops, sweet moisture, flowers bringto spring, which fruit brings forth and so shall we live hopefully all good to see.

and crossed, though in Antipodes not quite bereft, nor left, but in just course shall come again, and with pure light both shine and reign. |

N7 (pp. 51-53): This, like N6, is a song sung by Antissia still in her fit of madness. She addresses the song to Melissea, a magician and sage presiding over many of the more magical events in Urania, who will cure Antissia of her madness, which was Dorolindus’s purpose in bringing Antissia to see Melissea. The unusual structure with its two-syllable second and fourth lines in each stanza, might be intended to represent Antissia’s agitated state of mind, though at the same time the elaborate structure is perfectly controlled by Wroth. The speech that Antissia makes following on from the song is, however, much more clearly ‘deranged’ in its excessively flowery language (e.g. describing eyes as ‘flamigerous beacons’). Antipodes: the idea of the Sun spending winter in the antipodes reflects the notion that it is the sun revolving around the earth, rather than the reverse, which was posited by Copernicus in the mid sixteenth century. |

|

|

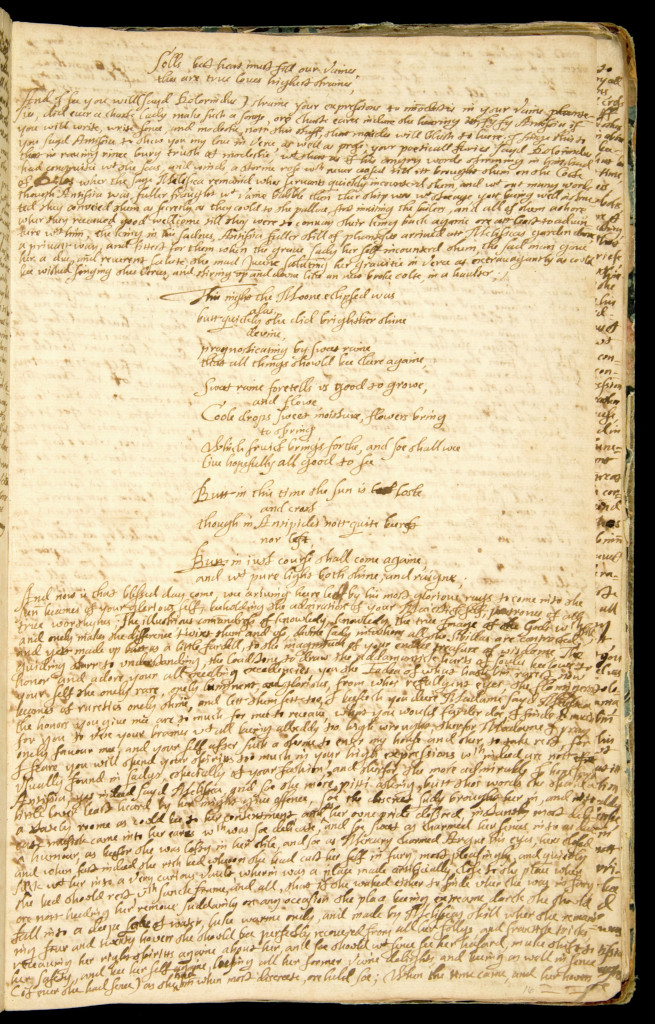

N8 Stay holy fires of my deʃires flame nott ʃoe fast my loves butt young from bud new sprunge ʃcarce knows loves taste,

till ʃacrifies were reddy made a love ʃcarce greene was never seene in withring shade,

if then orethrowne wt curst denyes poore hart ʃwell’out ʃend flames about wt murdering eyes,

To Court agen Wher loves inthround, if they perʃist and ʃmiles reʃist, while chast love is ʃcornd

wt fierce lov’s darts, and wt that store of harts wch shakes make martir stakes still framing more

wher all truth lies a blaʃe of fire frame As Heccatombbe for victors doombe to true loves name

of my deʃirs may riʃe, and flame Pheanix for truth conʃum’de in youth burnt to loves fame;/ |

N8

Stay holy fires of my desires flame not so fast; my love’s but young from bud new sprung, scarce knows love’s taste.

till sacrifices were ready made; a love scarce green was never seen in withering shade.

if then overthrown with cursed denies; poor heart swell out, send flames about with murdering eyes.

to Court again, where love’s enthroned; if they persist and smiles resist while chaste love is scorned.

with fierce love’s darts, and with that store, of hearts which shakes make martyr stakes still framing more.

where all truth lies a blaze of fire frame, as Hecatombe for victors doom to true loves name.

of my desires may rise and flame; Phoenix for truth consumed in youth burned to love’s fame. |

N8 (pp. 74-75): This is a song sung by the King of Tartaria’s sister. She is overheard by Licandro, the Prince of Athens, who falls violently in love with her (see N9). She is described in considerable detail and summed up as a woman whose ‘rarenes sett harts on fire’ (76). holy fires: this slightly disconcerting blending of the sacred and the profane evokes a Petrarchan image of desire. It seems unlikely that the image alludes to the so-called Holy Fire acclaimed as a miracle by the Orthodox Church since the fourth century. murdering eyes: like so much of Wroth’s poetry, eyes feature as both symbols of a gaze which positions women as objects, and as potentially redemptive when they can be used by the woman to counter that gaze. to Court again: this is another example of Wroth offering a political angle to her treatment of desire: here Love is the ruler and men are summoned to Love’s Court. A distinction is made in the poem between those who acquiesce to Love’s demands, and those who resist and will accordingly be attacked by fierce love’s darts: i.e. Cupid’s arrows, which will therefore take control of desire away from them. martyr stakes: this is potentially quite a chilling image given the very real execution of martyrs during the sectarian conflict characteristic of the early modern period. Hecatombe: deriving from the sacrifice of 100 cattle to the gods but generally meaning mass destruction. Phoenix: the mythical single bird that immolates itself in flames and then a new bird arises from the ashes. The poem itself mimics this movement, as it returns in circular fashion to the images with which it began. |

|

|

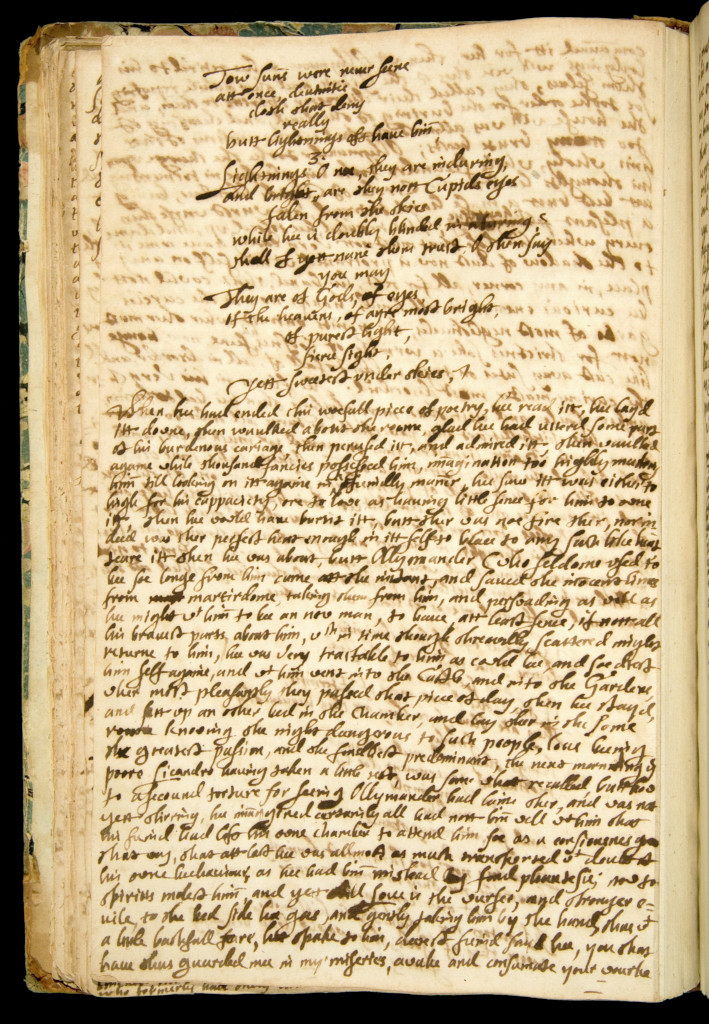

N9 Were ever eyes of ʃuch devinitie devine? noe they are of the Gods and ʃoe have ods, Of the Gods? Noe, more of Eternitie; They are blew, ʃure they are then heavens sky firmly kings they rule and com̅aund, motives of government doe ly to their imply readely, and ʃoe att mercy stand,

Bee they nott tow ʃuns, most shiningly Beam̅ing, noe they are meators rare wt out compare, Meators noe? thunderbolts killingly were they of Gods, they would deale beningly gently Tow ʃun̅s were never ʃeene att once, devinitie doth that deny really butt lightnings oft have bin̅,

Lightnings O noe, they are induring, and bright, are they nott Cupids eyes falen from the skies while hee is doubly blinded in aluring? shall I yet name them trust, O then ʃay you may They are of Gods, of eyes, of the heavens, of ayre most bright, of purest light, fierce ʃight, Yett ʃweetest under skies;/ |

N9 Were ever eyes of such divinity divine? No, they are of the Gods and so have odds. Of the Gods? No, more of eternity; they are blue, sure they are then Heaven’s sky, firmly kings they rule and command, motives of government do lie to their imply readily, and so at mercy stand.

Be they not two suns most shiningly beaming? No, they are meteors rare without compare. Meteors? No? Thunderbolts killingly; were they of God’s, they would deal benignly, gently. Two suns were never seen at once, divinity doth that deny really, but lightnings oft have been.

Lightnings? Oh no, they are enduring and bright. Are they not Cupid’s eyes fallen from the skies, while he is doubly blinded in alluring? Shall I yet name them trust? Oh then say you may; they are of Gods, of eyes, of the heavens, of air most bright, of purest light, fierce sight, yet sweetest under skies. |

N9 (p. 79): In this companion poem to N8, Licandro unburdens himself of his love for the Princess of Tartaria: it is described as a ‘woefull piece of poetry’ (79), i.e. full of the woe which he feels because his love is unrequited. Like the preceding poem, this one turns upon images of eyes, in this case the blue eyes of Licandro’s beloved. The poem also continues the interconnection between desire and political agency, especially the reference in the first stanza to ‘motives of government’. doubly blinded: Cupid is traditionally depicted as blind, so that the arrows he shoots that induce desire are distributed randomly. |

|

|

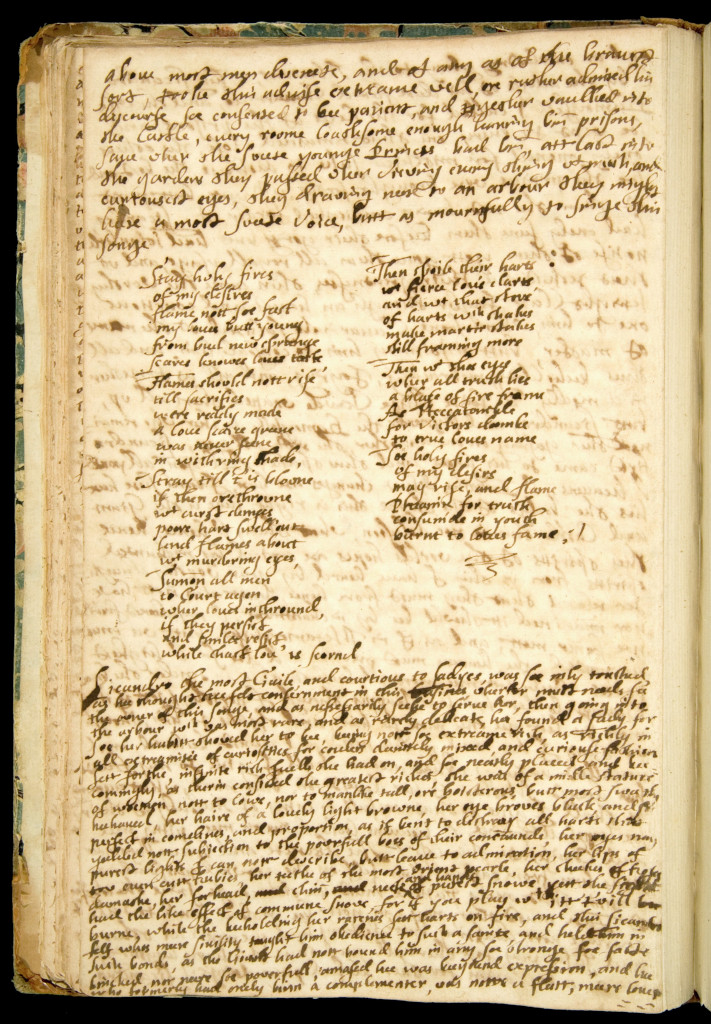

N10 Fierce love, alas yett lett mee rest, beeholde my boyling brest: Lett mee butt slumber, if nott sleepe continually to weepe is too great a ʃmart to a hart, Transform’d like Niobé to watry powers telling howers in drops of my misfortunes arte;

Cruell, alas, why doe thos eyes rule of the heavenly skies Joye in my ruin, my poore streames flumes can nott [blotted out word] coole [‘coole’ inserted above] our beames for loves ʃacred fire must aspire Transcendant to the highest powers telling howers In flames of my conʃuming fire

The Firmament may mee imbrace ther wanderers may finde place transform’d by love into a space borowing of lovers trace wher continuall faire will tell ayre wee destined by force, bred in ire may yet to evenings faire aspire,

Butt dull earth I see you contend nott willing I aʃsend, give mee then fruicts of plenty heere true increaʃe of beauties cheere, why doe you create ʃuch a bate

to ʃinge all harts by ʃuch a fire and intire conʃuming vs to our last fate;/ |

N10 Fierce love, alas, yet let me rest, behold my boiling breast; let me slumber, if not sleep, continually to weep is too great a smart to a heart, transformed like Niobé to watery powers telling hours in drops of my misfortune’s art.

Cruel, alas, why do those eyes rule of the heavenly skies? Joy in my ruin, my poor streams: flumes cannot cool our beams, for love’s sacred fire must aspire, transcendent to the highest powers telling hours in flames of my consuming fire.

The firmament may me embrace, there wanderers may find place transformed by love into a space borrowing of lovers’ trace, where continual fair will tell air we destined by force, earth, water, air, fire bred in ire may yet to evenings fair aspire.

But dull earth I see you contend; not willingly I ascend. Give me then fruits of plenty here true increase of beauty’s cheer. Why do you create such a bait, to singe all hearts by such a fire and entire consuming us to our last fate? |

N10 (pp. 81-82): This is another song, this time one sung by a group of women who are servants to the Princess of Argos. The song is overheard by two callow young Princes, Lusandrino and Nummerandro, who are entranced by the ‘heavenly voices’ (81). Niobe: In Greek mythology, Niobe boasted of her fourteen children to Leto, whose two children, Apollo and Artemis, respectively kill Niobe’s seven sons and seven daughters. Niobe turns to stone but weeps constantly so that water gushes from the stone, and so she became an image of constant grief, often associated with the complaint genre in poetry. flumes: i.e. the water vapour from tears cannot quench the fire of Love. sacred fire: this echoes the holy fire image of N8. earth, water, air, fire: these are the four elements. bait: desire is like a bait on a hook which will lead those captured to be singed by love’s fire. |

|

|

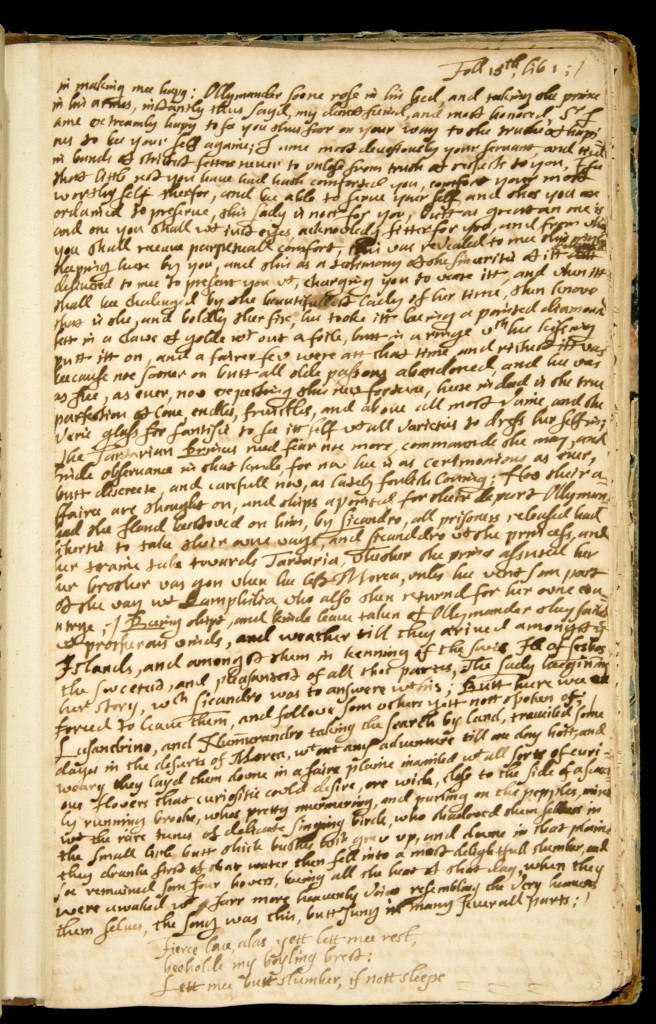

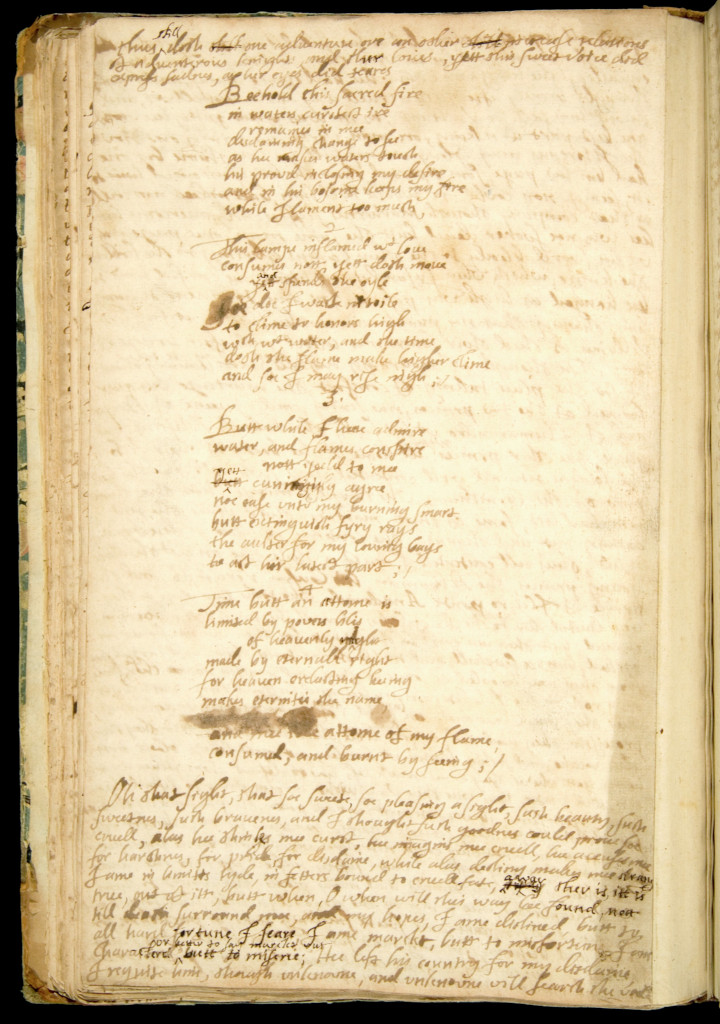

N11 Beehold this ʃacred fire in waters curstest ire remains in mee disdaining change to ʃee as hee makes waters touch his prowd incloʃing my deʃire and in his boʃome keeps my fire while I lament too much

This lampe inflamed wt love conʃumes nott yet doth move

ʃoe doe I waste [in] toile to clime to honors high wch wt water, and the time doth the flame make higher clime and ʃoe I may riʃe nigh;/

Butt while I heere admire water, and flames conspire nott yeeld to mee

noe eaʃe vnto my burning ʃmart butt extinguish fyry rays the aulter for my loving bays to act his latest part;/

Time butt an attome is limited by powers blis of heavenly mi̭ght made by eternall right for heaven erelasting beeing makes eternitie the name, [whole line smudged out] and mee the attome of my flame, conʃumed, and burnt by ʃeeing;/ |

N11 Behold this sacred fire in water’s curstest ire remains in me, disdaining change to see, as he makes waters touch, his proud enclosing my desire, and in his bosom keeps my fire, while I lament too much.

This lamp enflamed with love consumes not, yet doth move, and spends the oil, so do I waste in toil to climb to honours high, which with water, and the time, doth the flame make higher climb and so I may rise nigh.

But while I here admire, water and flames conspire: not yield to me, yet cunningly agree no ease unto my burning smart, but extinguish fiery rays the altar for my loving bays, to act his latest part.

Time but an atom is limited by power’s bliss of heavenly might, made by eternal right, for heaven everlasting being makes eternity the name, and me the atom of my flame, consumed, and burnt by seeing. |

N11 (pp.102-03): This is a song sung by Lindavera, the Princess of Frigia. She is disguised as a shepherdess and is overheard by three young princes: Antidorindo, Verolindo and Floristello. Her song is provoked by her love for the Prince of Albania, and we are told her ‘sweet Voice did express sadness, as her eyes did teares’ (102). sacred fire: presumably deliberately repeating the image from N10, this again emphasises the power of desire with a battle between the elements of fire and water forming a key part of the poem’s imagery. water’s curstest ire: the implication of this image is that the speaker/singer’s tears do not dampen the fire of Love. Curstest = most cursed. his proud: unclear but seems to mean Love’s pride ensures that she is trapped. If we take proud as an adjective, Love is proudly enclosing the speaker; if we take proud as a noun, it can refer to Love as a proud individual, with also some suggestion of sexual predatoriness. Stanza 2: this stanza explores the paradox at the centre of the poem’s depiction of desire: despite the water (tears) the flames grow stronger, just as the oil lamp burns fiercely yet the amount of oil remains the same (which is perhaps an allusion to the fact that the sacred lamp in the restored Second Temple was able to burn for eight days instead of the single day that the remaining oil should have fuelled). The paradox continues in stanza 3. in toil: in the manuscript a blotted t makes it possible that this word began as ‘not’ and was probably altered to ‘in’. loving bays: the bay tree (laurel) wreath, symbol of victory, especially a sign of an acclaimed poet, in this instance laid on the altar it seems to represent the speaker’s tribute/sacrifice for her unrequited love. atom: in the time when Wroth was writing, an atom referred to a minute particle and also the smallest unit of time (OED). The image in this stanza is then further developed so that at the end the speaker is an atom consumed by her unrequited love. burnt by seeing: the speaker is, in this final stage of the image of fire/desire, consumed by the sight of her love, who is rejecting her. |

|

|

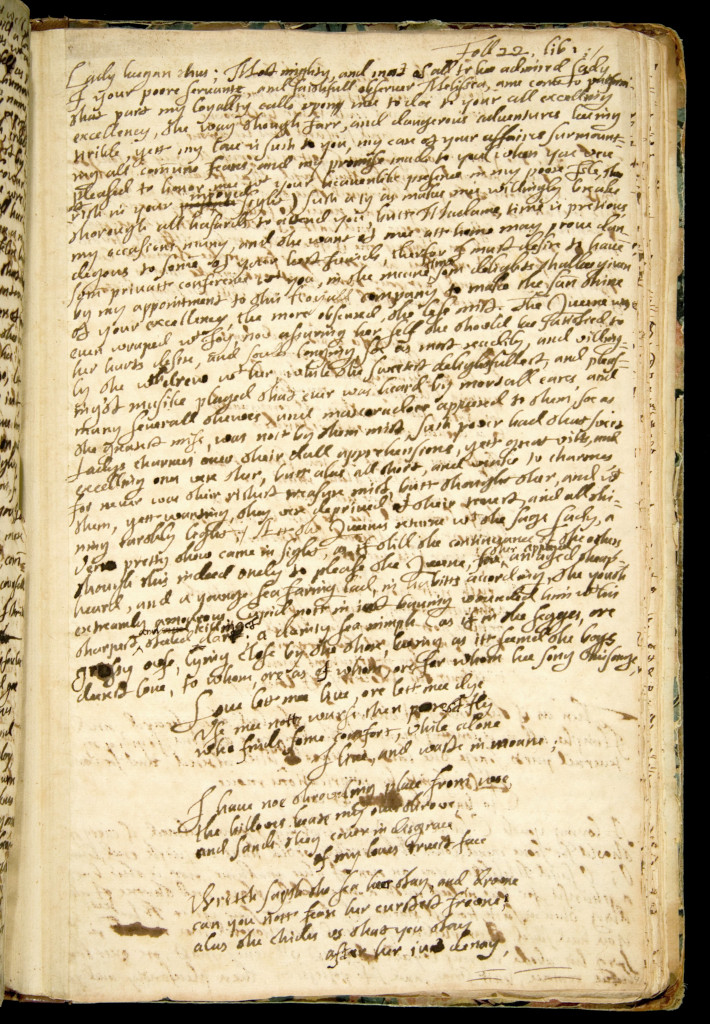

N12 Love let mee live, ore let mee dye, Vʃe mee nott wurʃe then porest fly who finds ʃome comfort, while alone I live, and waste in moane;

the billowes beare my ouer throwe and ʃands they cover in disgrace of my loves truest face

can you nott feare her curstest frowne? alas she chides vs that you stay after her iust denay,

how dare you mortall thus to moue bow hart, and ʃoule to her least frowne and ʃenʃur’d thus ly downe;/ |

N12 Love let me live, or let me die, use me not worse than poorest fly who finds some comfort, while alone I live, and waste in moan.

the billows bear my overthrow, and sands, they cover in disgrace of my love’s truest face.

can you not fear her curstest frown? Alas, she chides us that you stay after her just denay.

how dare you mortal thus to move? Bow heart and soul to her least frown, and censured thus lie down.' |

N12 (pp. 113-14): This song comes from another masque. This one is staged by Melissea, the enchantress who presides over the events in the narrative, and often brings about resolutions, and stages enchantments which test the characters. This song is sung by ‘a younge sea-faring lad’ (113) in the masque, who is in love with ‘a dainty sea nimphe’ (113). waste: i.e. waste away. shrouding place: i.e. a place to shield/protect him billows: referencing the ocean theme of the masque and the singer’s character as a seaman. denay: denial often spelled/pronounced as denay in the period e.g. Shakespeare, 12th Night II.iv.124 ‘My love can give no place, bide no denay’. sole of love: i.e. she is the only Goddess of love. |

|

|

N13 Love butt a phanteʃie light, and vaine fluttering butt in poorest braine, birds in Chimnies make a thunder, putting ʃilly ʃoules in wounder, ʃoe doth this love, this all com̅aunder to a weake poore understander;

ʃlight him, and hee’le your ʃervant bee adore him, you his slave must bee, ʃcorne him, O how hee will pray you, pleaʃe him, and hee’lle ʃure betray you let nott his faulshood bee esteemed least your ʃelf bee disesteemed

Crush nott your witts to place him high, a thought thing, never ʃeene by eye, implore nott heaven, nor dieties they know to well his forgeries nor ʃaints by imprications moue ‘t’is butt the Idolatry of love;/

to bace idolatrie of love;/ |

N13 Love but a fantasy light and vain, fluttering but in poorest brain, birds in chimneys make a thunder, putting silly souls in wonder. So doth this love, this all commander, to a weak, poor understander.

Slight him, and he’ll your servant be, adore him, you his slave must be, scorn him, oh how he will pray you, please him, and he’ll sure betray you. Let not his falsehood be esteemed lest yourself be disesteemed.

Crush not your wits to place him high, a thought thing never seen by eye, implore not heaven nor deities, they know too well his forgeries. Nor saints by imprecations move ‘tis but the idolatry of love.

to base idolatry of love. |

N13 (p. 114): This song follows on from the previous one (N12) and is part of the same masque. In this case, an ‘olde sheapheard’, who has been listening to the young seafarer of N12, responds to the young man’s plaintive song: he sings ‘with a rare Voice’ (114). Love but a fantasy: the old shepherd counters the power of love claimed in the preceding song by positing it as a fleeting and unimportant fantasy. Could also imply fancy. a thought thing: i.e. a figment of the imagination. idolatry of love: a slur directed at Catholic worship of idols by the firmly Protestant Wroth. |

|

|

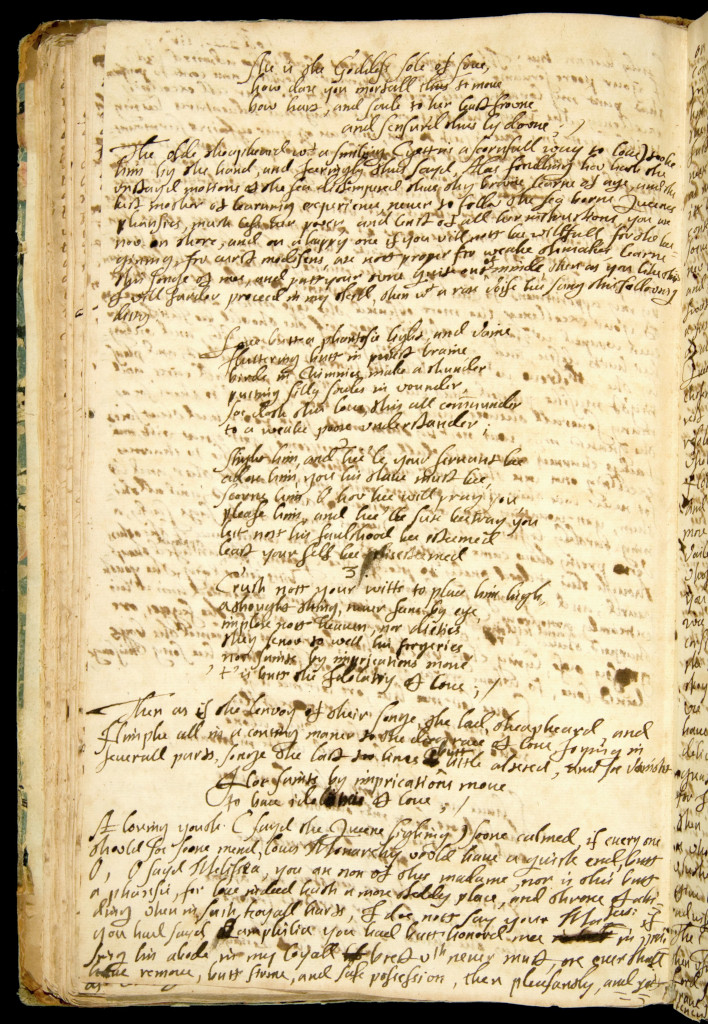

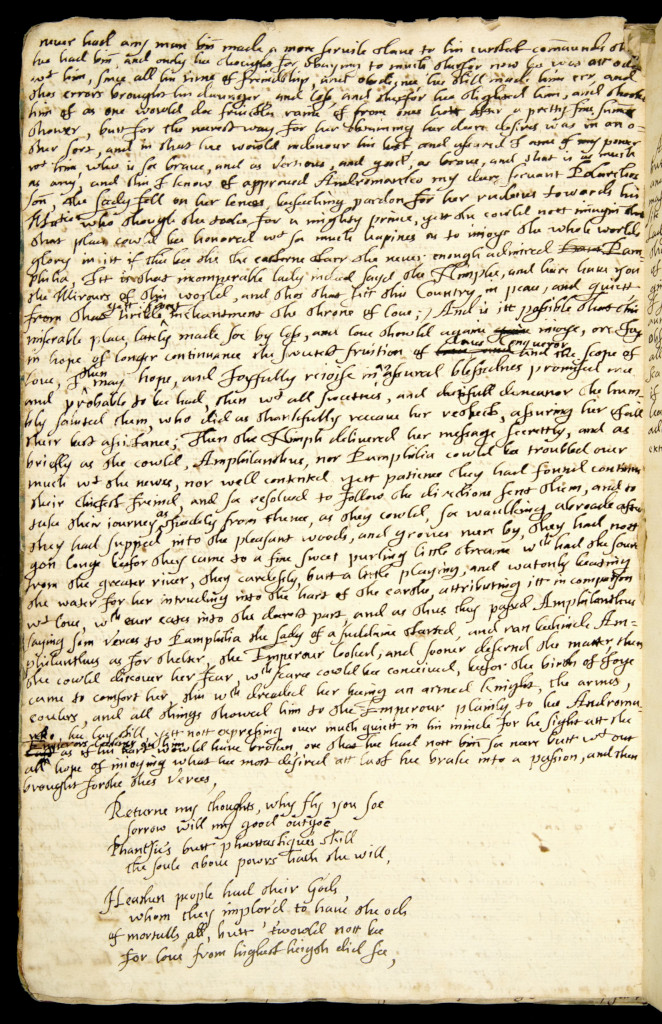

N14 Was I to blame to trust thy love like teares when t’is most Just to Judg of others by our owne while mine from heads of love

yett fruictles ran, could I ʃuspect that thine when in my hart each teare did write a line showld have noe spring butt outward showe,

in maske, wch made mee confident that thine had bin̅ love to , and noe disguiʃe, nott love put on, butt taken in, nor like a ʃcarfe to bee putt of wch lies, att choiʃe to weare ore leave, butt when thine eyes did weepe thy hart had bled wt in,

the sky that weeps itt doth nott paine butt weares the place where in the drops do fall ʃoe when thy Clowdy lids imparte thos showers of ʃubtill teares; and ʃeem to call compaʃsion when you doe not grieve att all you weepe them, butt they fret my hart,

to thinke you were as faire, ʃoe true why wowld you then your ʃelves in griefe attire wt pitty to inlarge my ʃmart when beauty had enough inflam’d deʃire and when you were even cumber’d wt my fire why would you blowe the coals wt art,

Itt was leʃs fault to leave then having left mee to deceave for well you might have my unworthe refuʃed nor cowld I have of wronge complaind butt ʃince your ʃcorne, you [two words crossed out] wt deceipt [‘wt deceipt’ inserted above] confus’d my undeʃert you have wt teares excuʃd, and wt the guilt your ʃelf have staind, |

N14 Was I to blame to trust thy love-like tears, when ‘tis most just to judge of others’ by our own, while mine from heads of love and faith did flow, yet fruitless ran, could I suspect that thine, when in my heart each tear did write a line, should have no spring but outward show?

in mask, which made me confident that thine had been love too, and no disguise, not love put on, but taken in. Nor like a scarf to be put off, which lies at choice to wear or leave, but when thine eyes did weep, thy heart had bled within.

But as the guileful rain the sky that weeps it doth not pain, but wears the place wherein the drops do fall, so when thy cloudy lids impart those showers of subtle tears, and seem to call compassion when you do not grieve at all, you weep them, but they fret my heart.

to think you were as fair, so true; why would you then your selves in grief attire with pity to enlarge my smart, when beauty had enough inflamed desire, and when you were even cumbered with my fire, why would you blow the coals with art?

It was less fault to leave than, having left me, to deceive, for well you might have my unworth refused, nor could I have of wrong complained. But since your scorn you with deceit confused, my undesert you have with tears excused, and with the guilt your self have stained. |

N14 (p. 137): This is a poem recited by Amphilanthus. (Unlike N2, there is no evidence that this was written by William Herbert and it did not circulate as widely as N2.) Amphilanthus is stricken because, believing that Pamphilia is betrothed, he is persuaded to marry the princess of Slavonia, but immediately regrets abandoning his vows to Pamphilia. This poem is a product of his melancholy and guilt: ‘I ame the shameless creature, the monster of sacred Vowes’ (138). Gavin Alexander has noted that the first stanza is used as the lyric in a song ascribed to Alfonso Ferrabosco, which exists in a manuscript held at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. (See Gavin Alexander, ‘The Musical Sidneys’, John Donne Journal 25 (2006): 96-102). Alexander reproduces the musical setting keyed to Wroth’s version of the lyric. Katherine R. Larson has discussed the song at some length in her study The Matter of Song in Early Modern England (OUP, 2019), and a recording of the song is available on the companion website to Larson’s book: https://global.oup.com/booksites/content/9780198843788/. A version of the poem with a number of variants is transcribed in an anthology that forms part of the Conway papers: see Daniel Starza-Smith, John Donne and the Conway papers (OUP, 2014), p. 241; like N2 this poems will be fully edited in Mary Ellen lamb and Katherine R Larson’s forthcoming edition of Herbert’s poems (MRTS, 2020). The first stanza is about Pamphilia’s purported (but misrepresented) betrayal. Again we have an image of Love connected to tears, but in this case the tears are divided intro true (Amphilanthus’s) and false (Pamphilia’s, which are only love-like not truly signs of love): he has been betrayed by an ‘outward show’. [I]: the manuscript does seem to read O rather than I although it is just possible that the curl at the top is makes it I. Roberts silently emends to I and I does make much more sense than O. in mask: this image continues the theme of the disconnect between outward show and truth, which is a common image in Wroth’s poetry, but usually from the perspective of the female victim of male duplicity. Amphilanthus himself is, generally, the guilty party, as his symbolic name (lover of many) implies. guileful rain: possibly linked to the Niobe image in N10, the idea here is that tears are false guides to sincerity, and that they do not show the grief of the person shedding them, but rather wear away the person (Amphilanthus) who witnesses them. and seem to call: Gosset Mueller edition of Urania Part Two and Roberts have ‘which’ seem to call. Manuscript looks more like ‘and’ but with extensive bleeding through from the other side of the page there is a possibility that it could be ‘which’, though ‘and’ seems more likely. cumbered: encumbered. blow the coals: again the fire/water imagery is used to show Amphilanthus’s despair as his flames are fanned. The final stanza turns on the paradox of the speaker being undeserving, yet nevertheless being deceived by the apparent grief displayed by Pamphilia. It was less fault: Roberts has ‘For ‘for ‘Itt’. unworthy: i.e. less worth, he is not worthy. |

|

|

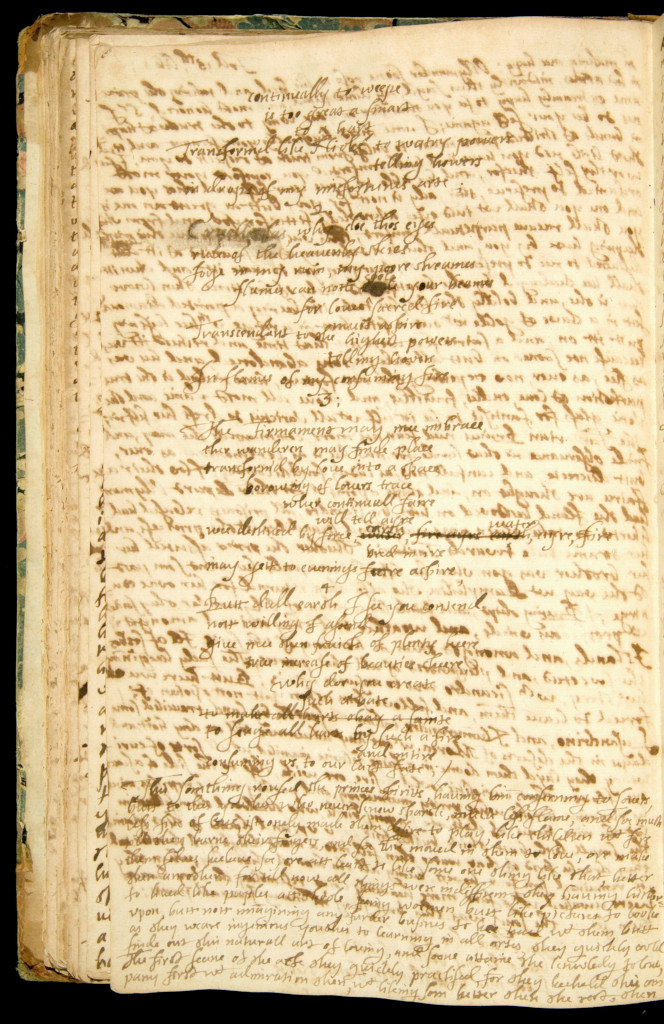

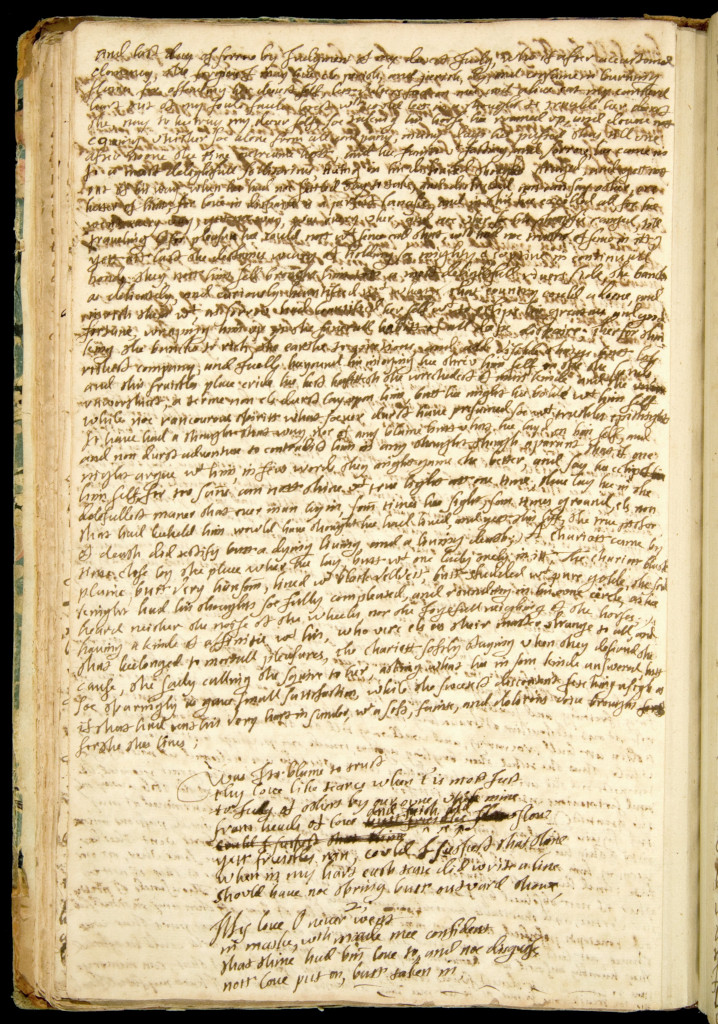

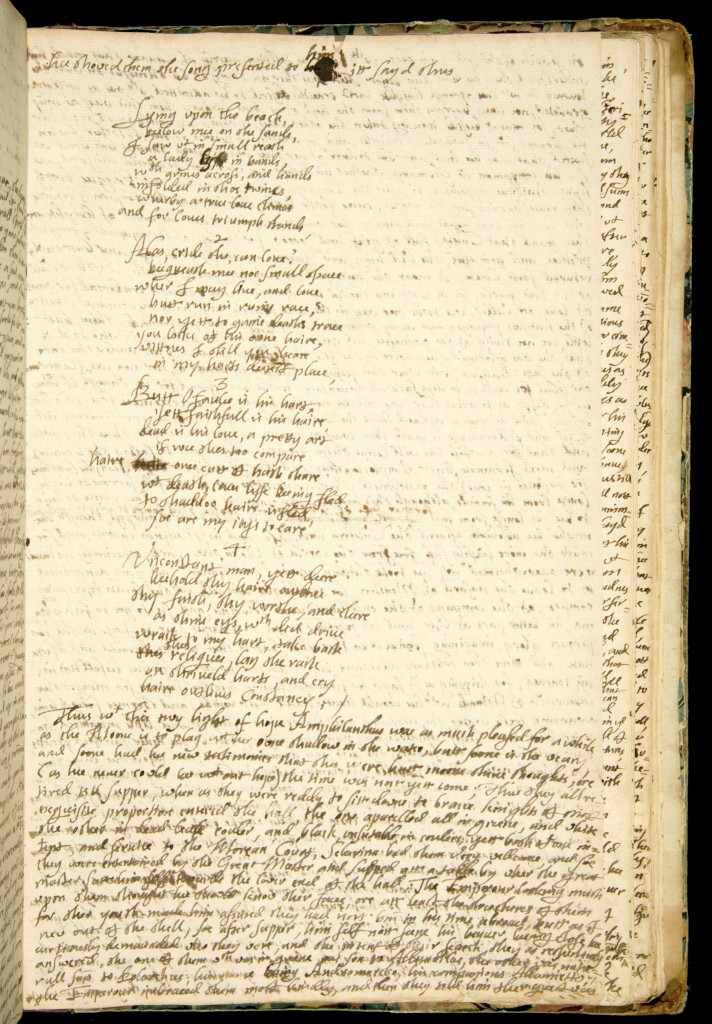

N15 Lying vpon the beach, below mee on the ʃands, I ʃaw wt in ʃmall reach A lady ly in bands, wth armes acroʃs, and hands infolded in thos twines, wherby a true love shines and for loves triumph stands,

bequeath mee noe ʃmall space wher I may live, and love butt run in ruins race? nor yet to gaine deaths trace you locks of his owne haire, wittnes I still you beare in my harts dearest place,

yett faithfull is his haire, dead is his love, a pretty art if wee these tvo compare haire [crossed out word] once cutt of hath share wt death, loves lyfe beeing fled, to shadow haire is fled, ʃoe are my joys to care.

beehold thy haire outlive thy faith, thy worthe, and cleere as thine eys, wth did drive wrack to my hart, take back

on shriveld harts, and cry haire outlives constancy;/ |

N15 Lying upon the beach, below me on the sands, I saw within small reach a lady lie in bands, with arms across and hands enfolded in those twines, whereby a true love shines and for loves triumph stands.

bequeath me no small space, where I may live and love, but run in ruins race? Nor yet to gain death’s trace. You locks of his own hair, witness I still you bear, in my heart’s dearest place.

yet faithful is his hair, dead is his love, a pretty art if we these two compare. Hair once cut off has share with death: love’s life being fled, to shadow hair is fled, so are my joys to care.

behold thy hair outlive thy faith, thy worth, and clear as thine eyes, which did drive wrack to my heart, take back, these relics, lay the rack on shrivelled hearts and cry: ‘hair outlives constancy!’ |

N15 (p. 144): This poem is part of a poetic exchange but the poems presented to Urania and Selarina do not exist: the manuscript has blank spaces for them, but Wroth has not inserted them (p. 142). This poem is presented by a shepherd to Amphilanthus as a kind of poetic tonic intended to cheer him up. The poem itself is a narrative which Josephine Roberts notes as being related to a song from the Portuguese romance Diana, by Montemayor (1559, English translation by Batholemew Yong, 1598). The song from Diana was loosely translated by Philip Sidney, and the first stanza was translated by Wroth’s father Robert Sidney (Philip’s brother). Philip Sidney’s version: What changes here, O hair, I see since I saw you: How ill fits you this green to wear, For hope the colour due. Indeed I well did hope, Though hope were mixed with fear, No other shepherd should have scope Once to approach this here, Ah hair, how many days My Dian made me show With thousand pretty childish plays, If I ware you or no, Alas how oft with tears, O tears of guileful breast She seemed full of jealous fears Whereat I did but jest. Tell me, O hair of gold, If I then faulty be That trust those killing eyes, I would, Since they did warrant me. Have you not seen her mood, What streams of tears she spent, Till that I swore my faith so stood As her words had it bent. Who hath such beauty seen In one that changeth so? Or where one’s love so constant been? Whoever saw such woe? Ah hair, are you not grieved To come from whence you be, Seeing how once you saw I lived, To see me as you see. On sandy bank of late I saw this woman sit, Where sooner die than change my state, She with her finger writ: Thus my belief was stayed, Behold Love’s mighty hand On things were by a woman said, And written in the sand. (Philip Sidney, The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, 1598, pp. 487-88, modernised by Paul Salzman). Robert Sidney’s single stanza: She whom I loved, and love shall still, Sitting on this then blessed sand, Wrote with to me heaven-opening hand, ‘First will I die ere change I will’. Oh unjust force of love unjust That thus a man’s belief should rest On words conceived in woman’s breast And vows enrolled in dust. (from ‘Poems of Robert Sidney’, ed. Katherine Duncan-Jones, English 30 (1981): 54, modernised by Paul Salzman. bands: i.e. bonds. shines: Roberts has ‘shines’, Urania edition has ‘climbs’: it is hard to decide between these but shines seems to make more sense in the context of the stanza and the overall poem’s treatment of the lock of hair. to shadow hair is fled: in this image, the hair cut from the lover is dead, like the love they once shared. behold thy hair: the tradition of a lock of hair signifying love and faithfulness is longstanding: the most commonly cited early modern example is Donne’s ‘The Relic’. wrack to my heart…lay the rack on shrivelled hearts,: in the first half of this image the faithless eyes are sees as shipwrecking the heart, and then the ‘shriveled’ heart is laid on a rack to be punished like a victim of torture who is stretched on the rack. |

|

|

N16 Come deere lett’s waulke into this spring wher wee may heere the ʃweet birds ʃing and lett us leave this darckʃum place wher Cupid never yett had grace For loves bright light must us delight, and Cupids fire must still respire, and brightest showe in darckest night

hee lives in highest spheares above, and from his beames gives worlds ther light, hee raigning Cround wt ʃweets delight, In darknes spite hee rules in light, for Cupids fire must still reʃpire And brightest show in dullest night,

nor hee’s perfect heat, and strives to moue wher equall flames wt him showes love In Coldes despite hee rules in might For Cupids fire must still aspire And pow’rfulst show in darckest night;/ |

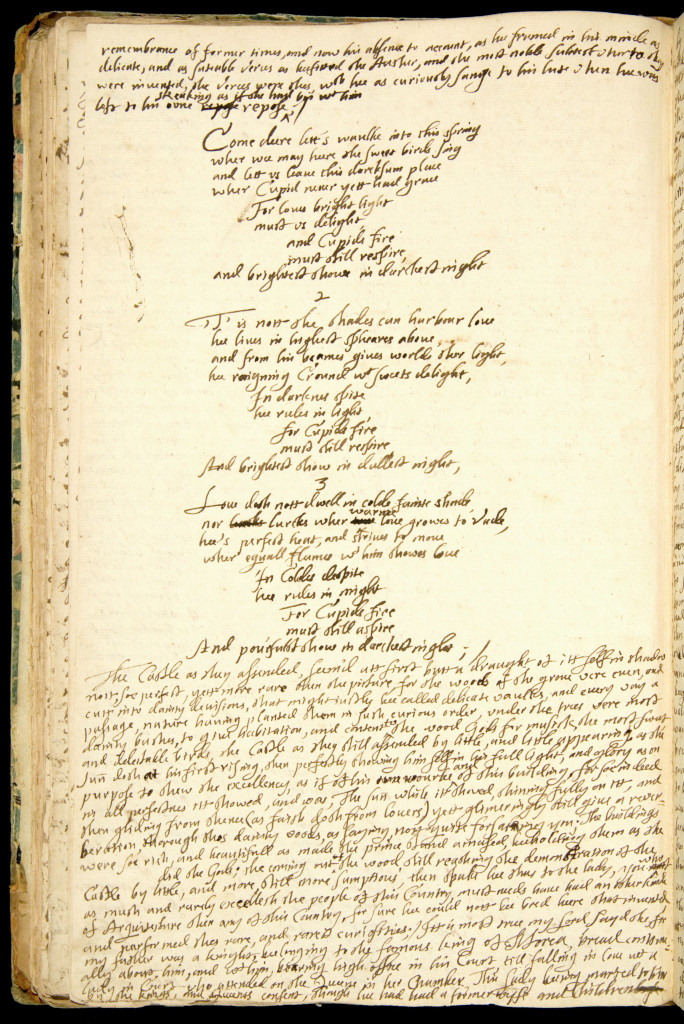

N16 Come dear let’s walk into this Spring where we may hear the sweet birds sing, and let us leave this darksome place where Cupid never yet had grace. For love’s bright light must us delight, and Cupid’s fire must still respire, and brightest show in darkest night.

he lives in highest spheres above, and from his beams gives worlds their light, he reigning crowned with sweet’s delight. In darkness’ spite he rules in light, for Cupid’s fire must still respire, and brightest show in dullest night.

nor lurks where warm love grows to fade he’s perfect heat, and strives to move where equal flames with him shows love. In cold’s despite he rules in might, for Cupid’s fire must still aspire, and powerful’st show in darkest night. |

N16 (p. 149): This is a song sung to the lute by Steriamus, King of Albania, addressing his wife Urania (one of the main characters in the romance). Cupid’s fire: unlike previous poems, in this instance fire has positive associations: fire and Cupid are associated with Steriamus’s fulfilled love for his wife. In darkness spite: i.e. in spite of darkness which Cupid/Love dispels. |

|

|

N17 Most hapy memory bee euer blest Wch thus brings into my most weary minde Joys past though others would them tortures finde, butt I delighted was in them, though rest

Yett lou’d the fetters did mee slave like binde, O love, what is thy force? ʃome ʃay thou’rt blind, noe thou canst ʃee best, and can give [crossed out word] eaʃe best,

and darken nott my first, and deerest choiʃe, from wch though ʃwerved, I in itt still reioyʃe, nor lett the fates from mee thoʃe phantʃies drive,

non must the former from my ʃoule unfolde;/ |

N17 Most happy memory, be ever blessed, which thus brings into my most weary mind joys past, though others would them tortures find, but I delighted was in them, though rest

yet loved the fetters did me slave-like bind. Oh love, what is thy force? Some say thou art blind. No, thou canst see best, and give ease best.

and darken not my first and dearest choice, from which though swerved, I in it still rejoice, nor let the fates from me those fancies drive.

none must the former from my soul unfold. |

N17 (p. 152): This poem, in the sonnet form of ABBA, ABBA, CDDC, EE, follows on shortly after the previous one: Steriamus recalls how (as depicted in the published Part One of the romance) he was at first in love with Pamphilia, until he was magically cured of this passion, and was able to return to his true love for Urania. This poem recollects the earlier love, and the idea that the memory remains even though he is loyal to his wife Urania. The memory (as evoked in the poem) does raise a quite powerful set of emotions in Steriamus, as he recalls his first love, ‘as hee was allmost like to have fallen into a dangerous passion. But Melissea had a careful hand over him, and soe he fell onely into a pretty little frenzy for the time of olde love and memory’ (152). The entire poem is like a re-evocation of first love. enfold: the final couplet with its enfold/unfold end words, which are almost but not quite homonyms, evokes the paradox of love as a palimpsest where the second love overwrites but does not erase the first. |

|

|

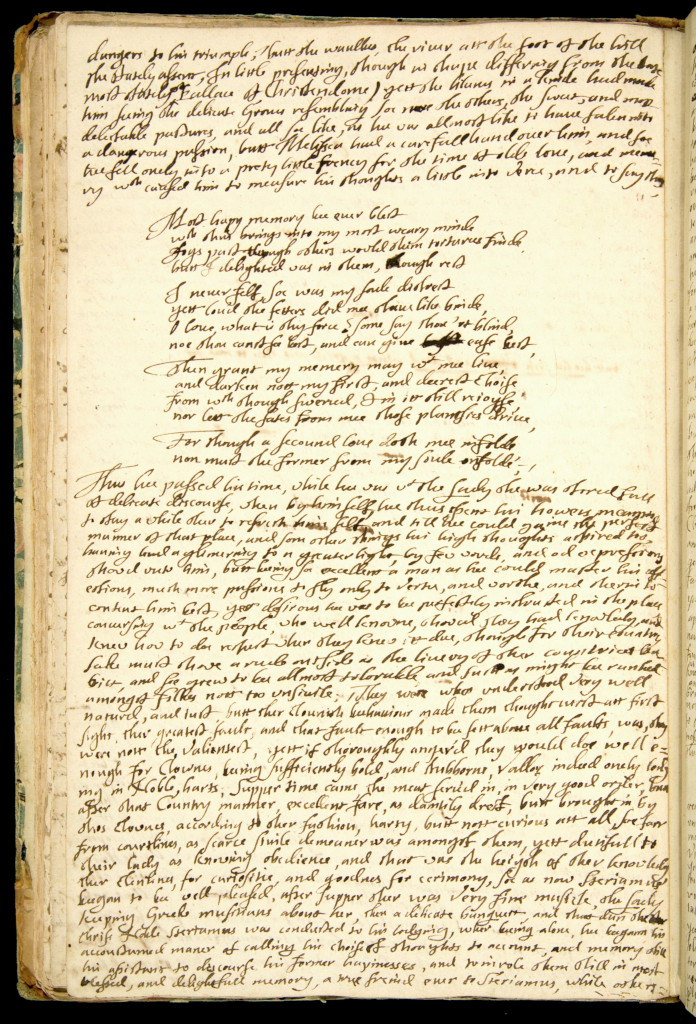

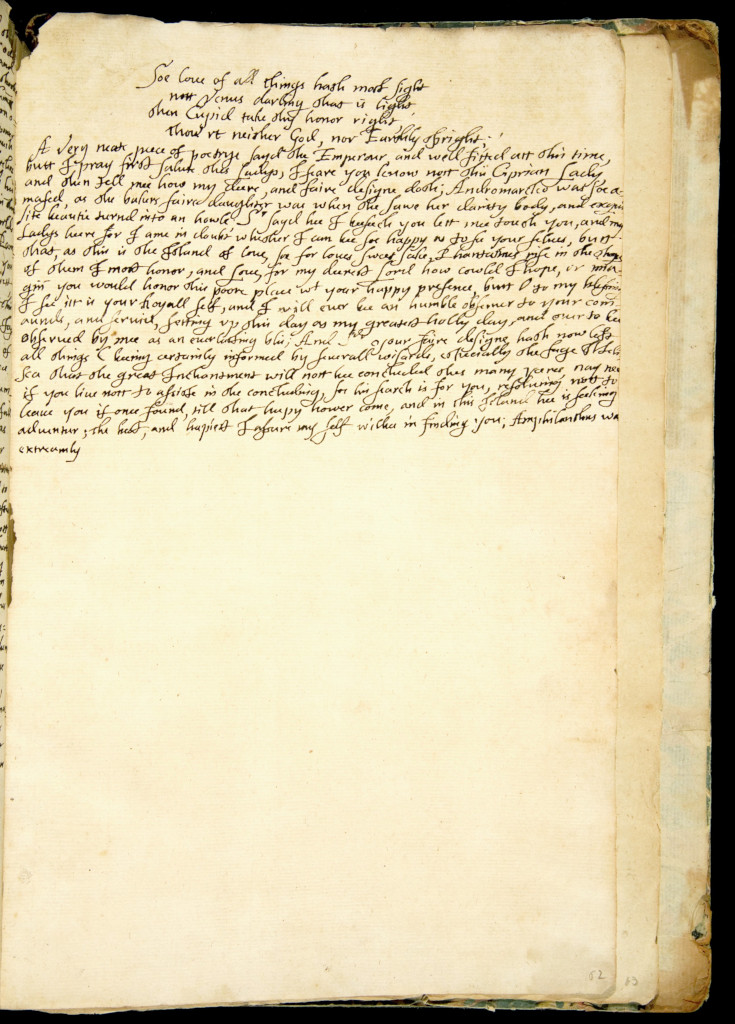

N18 Returne my thoughts, why fly you ʃoe ʃorrows may my good outgoe, Phantʃie’s butt phantasticks skill the ʃoule alone hath onely will,

whom they implor’d to have the odds of mortalls all, butt ‘t’would nott bee for love was high’st inthron’d to ʃee,

and noe thing more then love is light, then Cupid take thy honor right thou’rt neither God, nor Earthly sprite;/ |

N18 Return my thoughts, why fly you so? Sorrows may my good outgo, fancy’s but fantastic’s skill the soul alone has only will.

whom they implored to have the odds, of mortals all, but ‘twould not be for love was highest enthroned to see.

and nothing more than love is light, then Cupid take thy honour right thou art neither God, nor earthly sprite. |

N18 (pp. 411-12): As noted in the Introduction, there are only two poems in Book Two of the manuscript, and in fact they are two variations of what is essentially the same poem. In the first instance, this poem is recited by a so-called ‘Cyprian lady’. She is the daughter of the Duke of Sabro, and during a description to Pamphilia and Amphilanthus of how she fell in love with Andromarko, she explains that she composed this poem while wandering in a wood. The poem is blown by the wind into the hands of Andromarko, and while running to retrieve it, the lady sees him and is smitten. Andromarko is equally smitten (and it turns out that they had previously fallen in love with each other’s pictures). fantastic’s skill: in early modern usage, a fantastic was an illusion, so the idea expressed here is that fancy is a skilfully-created illusion. neither God not earthly sprite: in this image Cupid is seen as transitional: not a God (as Venus is) but still a spirit, not an earthly being. |

|

|

N19 Returne my thoughts, why fly you ʃoe ʃorrow will my good outgoe Phant’ʃie’s butt phantastique’s skill the ʃoule above powrs hath the will,

whom they implor’d to have the ods of mortals, all, butt ‘t’wowld nott bee for love from highest heigth did ʃee,

nott Venus darling that is light, then Cupid take thy honor right, thou’rt neither God, nor Earthly spright;/ |

N19 Return my thoughts, why fly you so? Sorrow will my good outgo, fancy’s but fantastic’s skill, the soul above powers has the will.

whom they implored to have the odds, of mortals all, but ‘twould not be for love from highest height did see.

not Venus’ darling that is light, then Cupid take thy honour right, thou art neither God, nor earthly sprite. |

N19 (p. 418): This variation on N18 is not included as a separate poem in Roberts’s edition. Here Andromarko is overheard by Amphilanthus and Pamphilia reciting this poem, which it would seem is intended by Wroth to be a variation on the previous poem: while this is not stated, one can perhaps assume that Andromarko, having obtained the previous poem, is reciting a slightly altered version of it. It is at this point that the manuscript breaks off, so we learn nothing more of this particular pair of lovers. highest height: changed from highest enthroned in N18. Venus darling: this alteration from N18, which does not explicitly mention Venus, stresses that Cupid is we might say a creature who mediates between humans and the Goddess Venus. While overall N19 is almost the same as N18, the mention of Venus coming from Andromarko’s mouth, rather than the lady’s, indicates how powerful desire is in this narrative, as we see it constantly undoing women and men equally. |

|

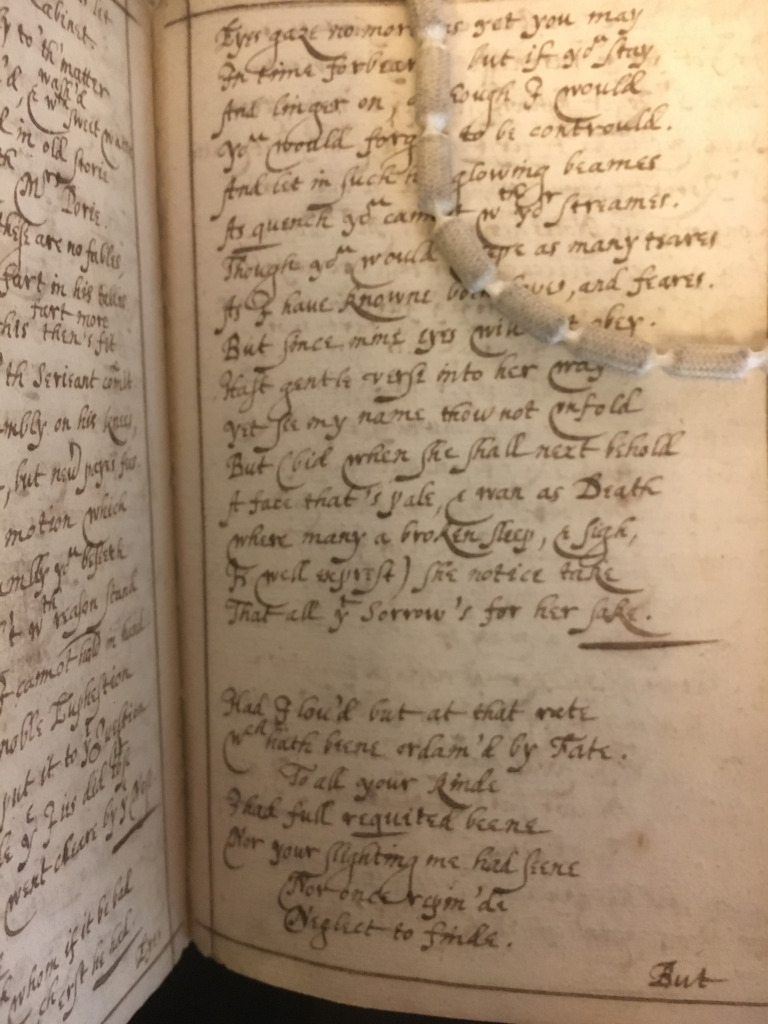

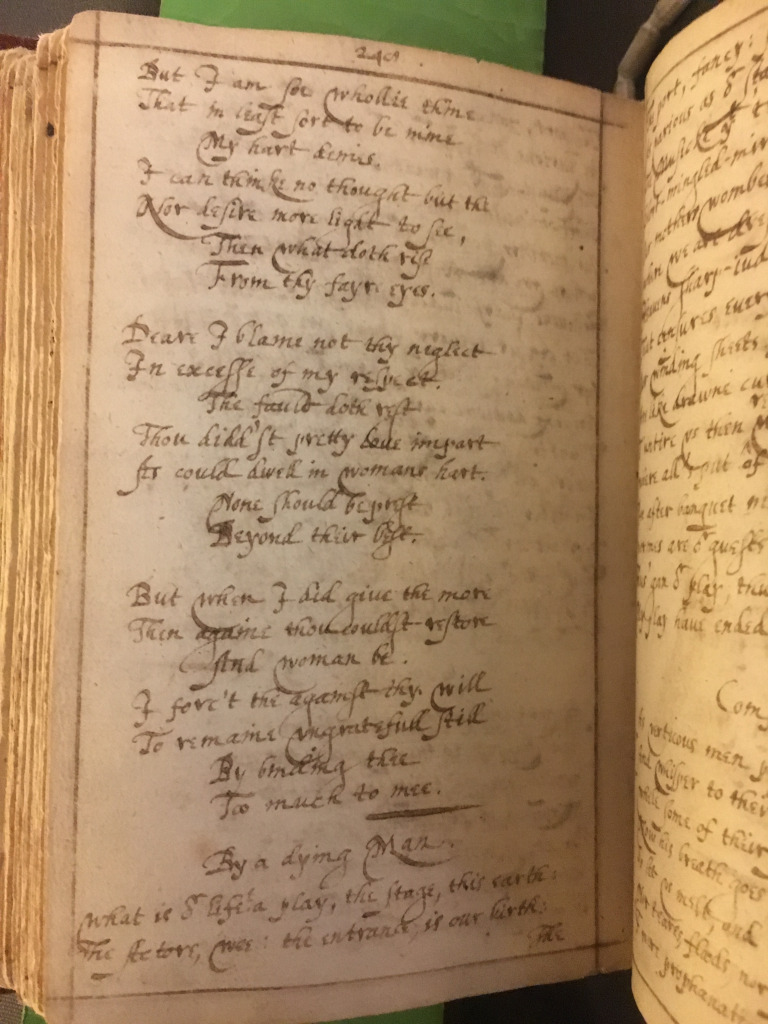

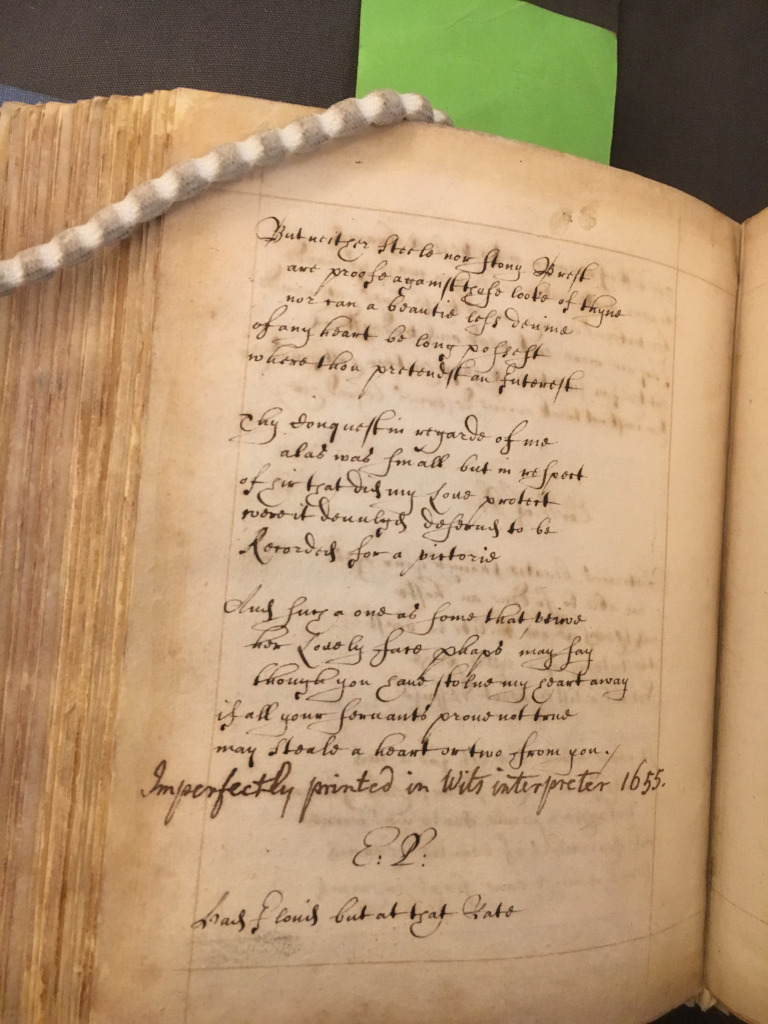

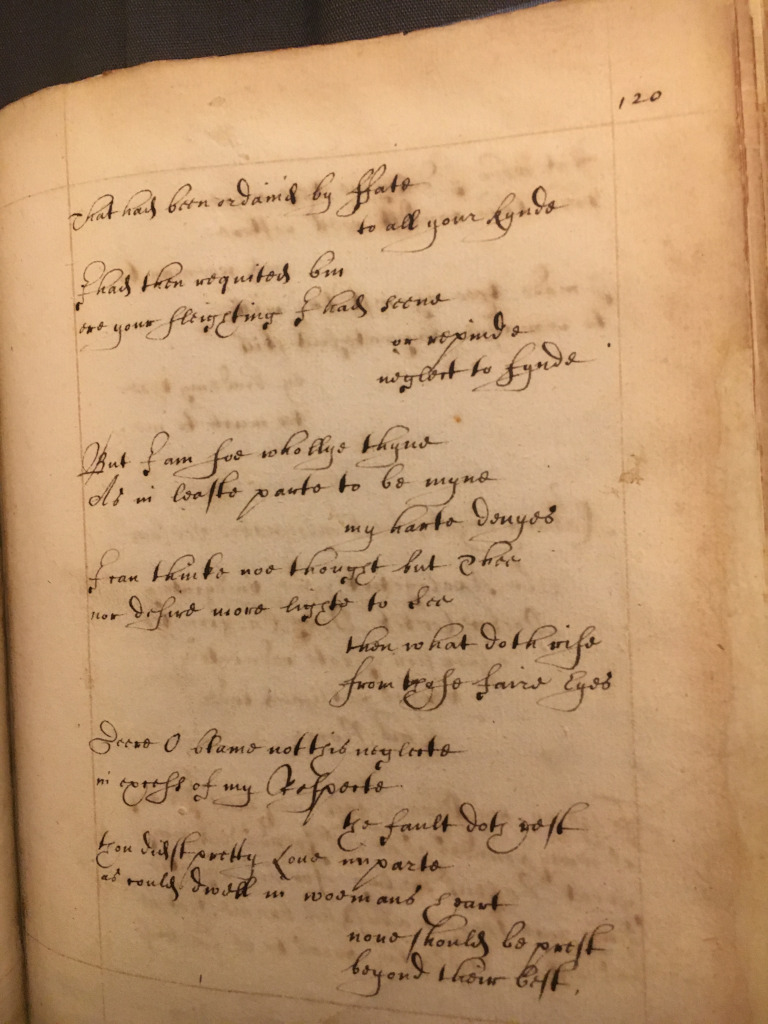

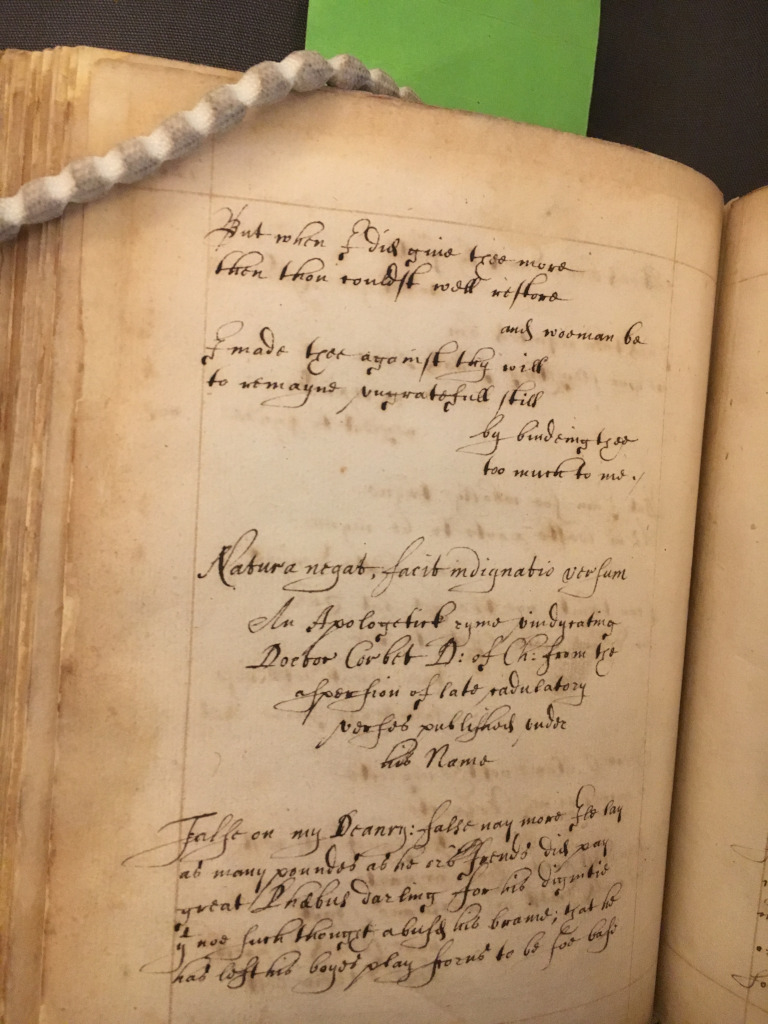

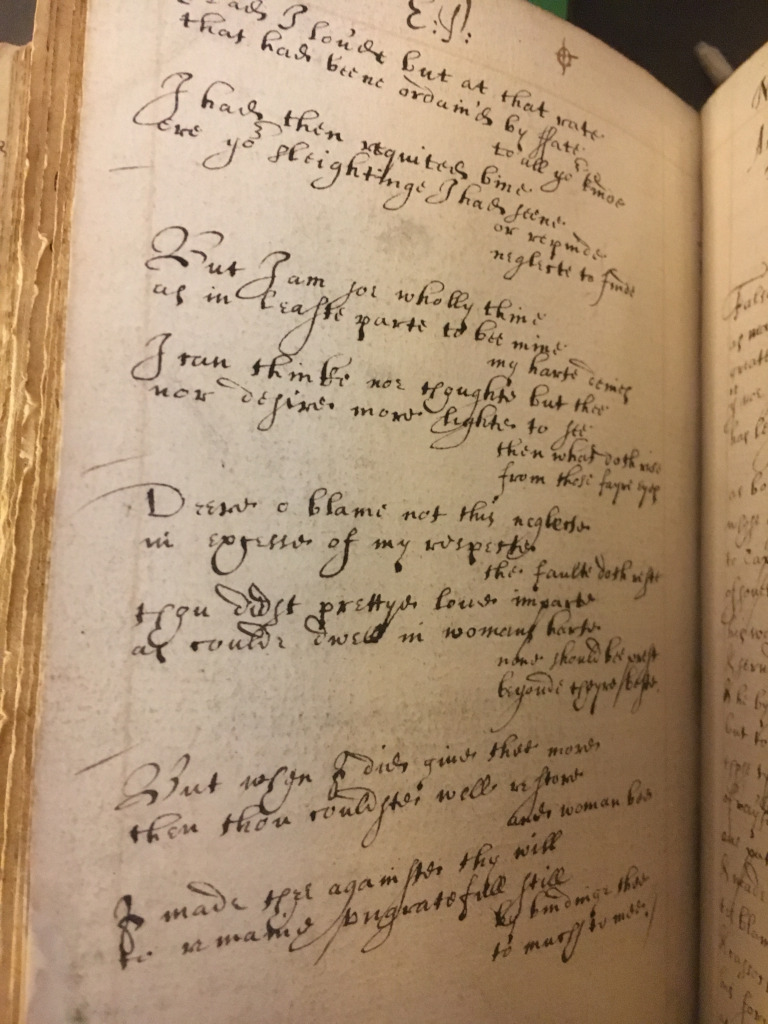

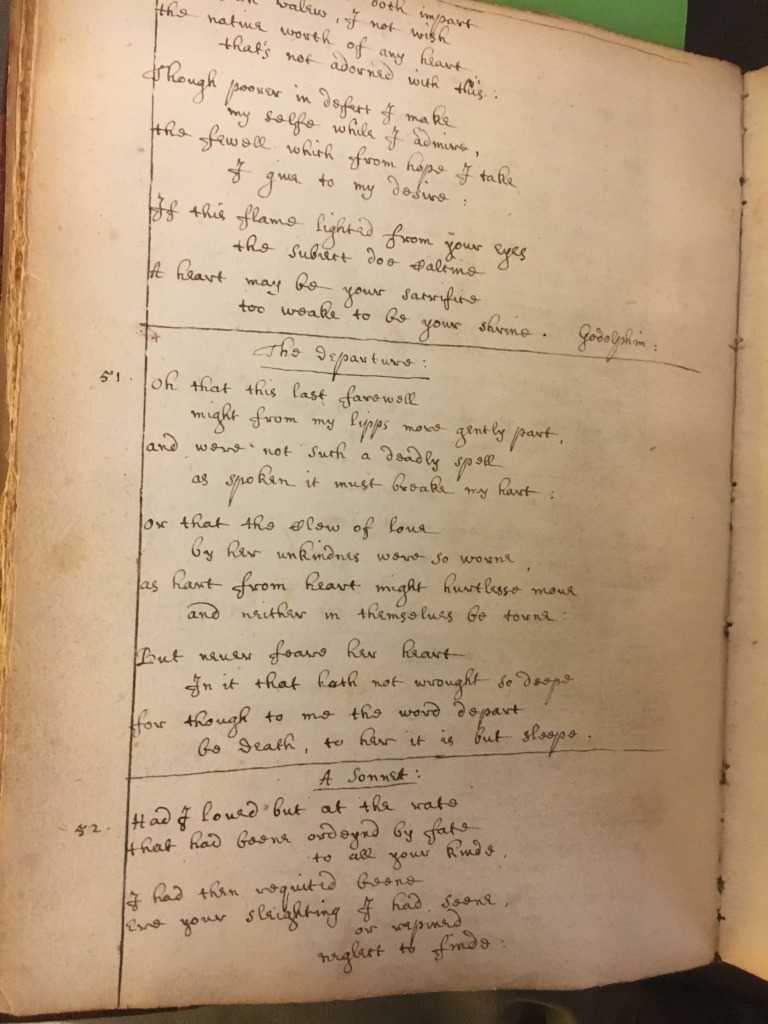

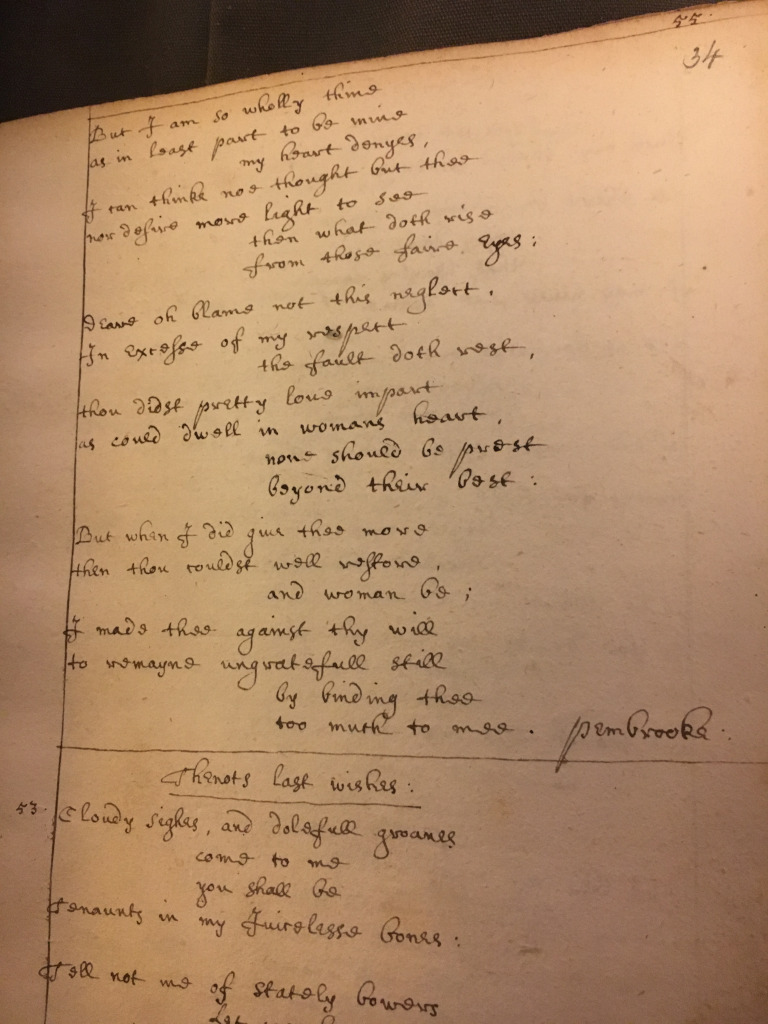

| APPENDIX: Images of manuscript versions of ‘Had I loved’ (ascribed to William Herbert) in four British Library manuscripts. |

|

|

|

|

BL Additional MS 10309, fol. 125 |

|

|

|

|

BL Additional MS 10309, fol. 125v |

|

|

|

|

BL Additional MS 21433, fol. 119v |

|

|

|

|

BL Additional MS 21433, fol. 120 |

|

|

|

|

BL Additional MS 21433, fol. 120v |

|

|

|

|

BL Additional MS 25303, fol. 130v |

|

|

|

|

BL Harley MS 6917, fol. 33v |

|

|

|

|

BL Harley MS 6917, fol. 34 |

|

|

|

| IMAGE |

|

|

|

| IMAGE |

|

|

|